Hamlet, Ophelia, Othello, Lear, the Macbeths, and Me

Shakespeare's Journeys into the Mind

Reveal His Grasp of Mental Illness

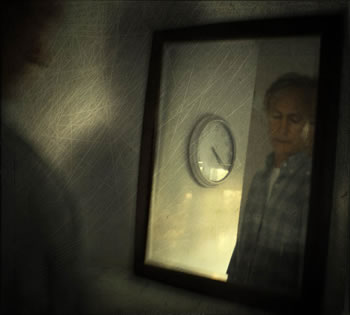

The psychotic forces that William Shakespeare depicts in some of his characters I witnessed on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., a few years ago. I was waiting for a friend outside a restaurant when I saw a man with a crazy leer wandering down the sidewalk, accosting people with angry, accusatory vulgarities. He started to approach me, but when he looked me in the eye, he went silent and altered his course, walking in a wide circle around me. He warily looked back at me over his shoulder as he moved along. I suffer chronic depression and was in one of my dark moments at the time, so he must have believed I was crazier than he. It was like Poor Tom sizing up Macbeth.

The psychotic forces that William Shakespeare depicts in some of his characters I witnessed on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., a few years ago. I was waiting for a friend outside a restaurant when I saw a man with a crazy leer wandering down the sidewalk, accosting people with angry, accusatory vulgarities. He started to approach me, but when he looked me in the eye, he went silent and altered his course, walking in a wide circle around me. He warily looked back at me over his shoulder as he moved along. I suffer chronic depression and was in one of my dark moments at the time, so he must have believed I was crazier than he. It was like Poor Tom sizing up Macbeth.

For those who have not experienced mental or psychological impairments (and for those who deny their own such issues) understanding exactly what is happening in the minds of those who do suffer such conditions is close to impossible. That's why so many people pooh-pooh such illness as fabrication or lack of mental or moral strength. I used to believe that, too, even after my first panic attack. It's notable, too, that many of us who do have chronic depression can identify each other without speaking about it; we have that secret handshake, as it were.

How can I describe the mental illness experience to the uninitiated? I can offer examples of incidents: a sudden, out-of-nowhere urge to drive into the path of an oncoming train, even with loved ones in the car. I can offer descriptions of a mental state: the absolute uncertainty that what you think you saw or heard is fact or fiction. I can offer descriptions of a physical state: you walk as if your head is a crystal bowl full of family heirlooms that you hope doesn't slip off and shatter into shards on the ground. I can offer descriptions of an emotional state: you aren't just concentrating on getting through the day, you are concentrating on getting through that minute, and then the next, and then the next. I can offer metaphor: Thin ice. You are skating along and you suddenly know—you don't suspect, you know—that you could fall through that instant. Sometimes you can see water flowing underneath; sometimes snow covers the ice, an illusion of beauty, a feint of security. You hear shotgun cracks coming from across the glaze—stress fractures—and you freeze. Do you keep going, knowing the next step might be fatal? Do you even have a choice? You are in the middle of a lake, so staying there is ultimately fatal, too. How you got there is immaterial: maybe you foolishly walked out from the shore, maybe you unwittingly walked across a snowscape, maybe you were suddenly apparated by a force beyond your understanding, if not your control. You hope you can make it to shore because if you can't you will need someone to pull you out of the swirling currents or life-sucking mud you'll fall into.

In fact, all I need to give you a true sense of what it's like when your brain goes awry is Shakespeare.

Lauded for his deep understanding of the human condition, Shakespeare also had a deep understanding of how the mind works, including mental and psychological disabilities. I don't contend he suffered such issues himself—he and I have not shared the secret handshake—even though his propensity for delving into troubled mental states came after his son's death. I believe, at the least, that with his great sense of empathy and his gift for observation and reading, as he matured he gained a keen grasp of mental illness, with or without personally experiencing it himself.

King Lear (Michael Pennington, with hands on his head) is guided by Edgar disguised as Poor Tom (Jacob Fishel) as the Fool (Jake Horowitz, right) watches in the Theatre for a New Audience production of King Lear. Kent (Timothy D. Sickney, left) attends on the trio as they take refuge in a hovel and engage in a hallucinatory trial. Photo by Carol Rosegg, Theatre for a New Audience.

I also see a bit of artistic audacity. Like Mozart showing off his skills in counterpoint, Shakespeare gives a virtuoso's three-part presentation of mental disabilities in one scene of King Lear. The title character has descended into madness and become delusional. Poor Tom may be Edgar in disguise but he plays the psychotic homeless beggar to the full (and it is a disguise representing Edgar's true experience as a homeless fugitive himself). The Fool, in Shakespeare's time, would have been a person with developmental disabilities (mental retardation or autism), and though today we tend to see Shakespeare's fools solely as jesters and clowns, a close reading of remarks about Touchstone in As You Like It and Feste in Twelfth Night reveals the true nature of these characters. Lear, Poor Tom, and the Fool stage a hallucinatory trial, and when the Fool is played as a young man with developmental disabilities, as was done in this year's Theatre for a New Audience production, it reveals Shakespeare's mastery in representing the unreal reality of the mentally impaired.

Shakespeare first depicts "madness" in Titus Andronicus, but Titus is faking madness (so he says, but he at least has a serious case of post-traumatic stress syndrome). Furthermore, like much of the play, his madness is a caricature and highly rhetorical. A Midsummer Night's Dream touches on madness as a theme, and what the lovers and Bottom go through resemble hallucinatory states. For Henry IV, Part Two, Shakespeare draws on the historical record of the king's bouts with mental illness in portraying him as suffering depression-induced insomnia.

Shakespeare ventures boldly into the realm of mental illness with Hamlet. One of the great debates of literature is whether Hamlet is actually mad or "mad in craft." I contend he is both, and that was Shakespeare's intent. Derek Jacobi in the 1980 BBC version of Hamlet plays him as "a mentally unstable man, one who not only trips from a state of clarity to a state of insanity and back again in the flash of a moment, but one who yet knows that this is happening to him." I'm quoting from my own review because it says as much about me as it does my observation of Jacobi's performance. I've not had a father murdered by my uncle, a mother married to that murderer, and a kingdom yanked away from me, yet Hamlet's soliloquies all strike uncomfortably close to home: "O, that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw and resolve itself into a dew"; "O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I"; "To be or not to be, that is the question."

Ophelia (Kimberly GIlbert) succumbs to insanity in the Taffety Punk Theatre Company production of Enter Ophelia, distracted, a take on Hamlet from the perspective of Ophelia as her mind slowly disintegrates. Photo by Teresa Castracane, Taffety Punk Theatre Company.

Of course, the play's one character who is truly insane is Ophelia. I've long thought her little more than a curiosity. I, like Gertrude, see Ophelia as one of those hallucinating individuals you cross the street to avoid or refuse to look at on the Metro in hopes they will leave you alone. My one personal experience with an Ophelia-like situation was back in college encountering a friend having a bad drug experience on the campus quadrangle and trying to keep her calm until the cops got there. In that instance I was more Horatio than Ophelia.

This summer I saw Ophelia in a new light—my own light—with the four-actress representation of the character in Kimberly Gilbert's Enter Ophelia, distracted by the Taffety Punk Theatre Company in Washington, D.C. Gilbert shows us Hamlet through Ophelia's perspective, and instead of a mad Ophelia suddenly showing up in Act IV, Scene Four, we see her gradual mental deterioration from the inside out. In one scene, the four actresses playing Ophelia parade in a square, and sudden jarring noises cause them to convulse. Here was my secret handshake moment with Ophelia. Stress compounded by lack of sleep or, worse, troubled sleep heightens your reactions to external stimuli—and internal stimuli, too, when bad memories or inexplicable worries come galloping into the forefront of your conscious. Even if it's all in your head, you physically wince.

Ben Jonson wrote that Shakespeare "was not of an age, but for all time!" Timing is, in fact, a prism through which Shakespeare's universal genius is revealed to us. You can see and read his plays countless times, but because of Shakespeare's rich renderings and poetic mastery, fuller understanding of his characters and verse comes at the intersection of the performance you are seeing or the edit you are reading and that very moment in your own time and mind. Such a confluence followed my attending Enter Ophelia, distracted. The next day I saw the American Shakespeare Center production of Macbeth at the Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Va. A week later I saw the Riverside Theatre in the Park production of Othello in Iowa City, Iowa. Between those performances, I fell into a bout of depression, my first sustained episode in so long I had forgotten how debilitating they could be.

Othello (Daver Morrison, left) has given in totally to his delusions, grown out of mere suspicion and the suggestions planted by Iago (Tim Budd, right) in the RIverside Theatre in the Park production of Othello. "When I love thee not, chaos is come again," Othello says of Desdemona, but in less than 500 lines he is, here, demanding of Iago to "furnish me with some swift means of death for the fair devil." Photo by Bob Goodfewllo, Riverside Theatre.

Whereas Enter Ophelia, distracted is Gilbert's interpretation of a character's mental state, Shakespeare himself shows us evolving psychosis in Othello. Proud and noble warrior that he is, and so smitten in love with Desdemona, Othello lets mere suspicion work in him from the inside as Iago works on him from the outside. The speed with which illusion becomes Othello's reality is not purposed just for theatrical necessity but is central to Shakespeare's portrayal—the whole of his transformation happens in one scene, less than 500 lines of verse. Tragic incidents and traumatic moments are not requirements for psychosis: a seed of concern self-planted or put there by someone else and fertilized with insecurity can in less than 500 lines of real life lead to a fully infested brain.

To a lesser degree, we can also see Iago's psychopathy evolving, but that's through his own report. He mentions in his first soliloquy the "thought abroad" that his wife, Emilia, and Othello have had an affair. In his second soliloquy, he describes how he is using that vague suspicion to fuel his own psychosis: "the thought whereof doth—like a poisonous mineral—gnaw my inwards" (apt word, inwards, an internal progression or, I guess, regression). Iago is definitely a villain and he is clearly ticked off at being passed over for promotion (a matter I've discussed in a previous commentary), but he also is a master psychologist. Seeing Othello approach, Iago can tell from his demeanor that not even drugs "shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep which thou owed'st yesterday." Yes, troubled sleep is one of the symptoms of depression and psychosis.

That becomes a central theme in Macbeth. Lady Macbeth does not go mad. In her one moment popularly attributed to "madness," she is sleepwalking and having a nightmare. Lady Macbeth suffers profound depression. The doctor tells Macbeth that she is "Not so sick, my lord, as she is troubled with thick-coming fancies that keep her from her rest," which is a perfect description of the undue worries that often haunt my nights and crowd peace from my sleep. Macbeth replies: "Cure her of that. Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain, and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart?" If Macbeth were living today, the doctor would answer with "Yes, we have an array of medications we can prescribe in conjunction with a period of psychotherapy." In the 11th century–set, 17th century–written play, the doctor pointedly says, "Therein the patient must minister to himself." That's true even today and even when using medication; when suffering depression we still must minister to ourselves (with help from trained therapists). But when we slip into psychotic impairment or "madness," we cannot minister to ourselves.

Another of the great debates in literature is whether or not the Weird Sisters merely untapped Macbeth's intentions or prodded him to murder. Some scholars are absolute in their beliefs that the Weird Sisters tell Macbeth what is already in his mind, and I've seen it played that way, on the clue of Banquo's "Good sir, why do you start and seem to fear things that do sound so fair?" However, in text-centric productions (and in my reading of the play), while Macbeth has a desire to be king he is not predisposed to regicide. Indeed, he had just saved his king from invasion and treason. Macbeth to me is no different than anybody wishing to be CEO of their company or a third-stringer desiring to be a Hall of Fame quarterback—that doesn't mean he is predisposed to killing the starter and putting the blame on the other quarterbacks ahead of him in the depth chart. Heck, if Weird Sisters told me, "Hail, Eric! Pulitzer Prize winner!" I'd start and seem to fear the thing that sounds so fair, too. For though I have that desire, I would consider it as impossible as being Thane of Cawdor and king hereafter would seem to Macbeth at the moment he hears those salutations.

Top, Lady Macbeth (Sarah Fallon), talking and walking in her sleep, experiences a nightmare. Bottom, Macbeth (James Keegan) rages with himself as he slips further into paranoia in the American Shakespeare Center production of Macbeth at the Blackfriars Playhouse. Photos by Lindsey Walters, American Shakespeare Center.

I bet those who believe Macbeth is already considering killing King Duncan have never encountered Weird Sisters in their own lives. Not that I have encountered any witches, per se, but I have experienced clear-signal omens and heard Field of Dream voices. These messages, like the Weird Sisters' prophecies, usually end up providing accurate guidance, too, leading me into successful ventures and foretelling me of coming troubles requiring alert navigation. Two things that separate me from Macbeth, at least on the surface, is that I'm not a warrior given to killing people nor do I have a Lady Macbeth for a wife (in passion, yes; in temperament and attitude, though, Sarah is more like Celia from As You Like It). Ignoring the "hereafter" portion of the prophecy, Lady Macbeth interprets the omens as an immediate state, which, perforce, requires killing the king.

What I call messages might be no more than my keen sense of instinct and the fact I am psychically attuned to my environment and human behavior. Sarah does coach me to follow my instincts, but not with the ambitious fervor of Lady Macbeth. Experience, meanwhile, has taught me that the line between psychic gifts and delusions is fuzzy at best, requiring enforced reasoning on my part. Disciplined instinct is a hard quality to maintain, and like all personal qualities, from eating and exercising habits to ethical standards, it ebbs and flows according to external and internal forces, and that line blurs all the more.

For well I know, "oftentimes, to win us to our harm, the instruments of darkness tell us truths, win us with honest trifles, to betray's in deepest consequence." This is Banquo warning Macbeth. Beyond serving as a plot device and object of flattery for Shakespeare's patron, King James I (a descendent of Banquo), Banquo is a psychological barometer for Macbeth. Banquo accepts the truth of the vision, but he maintains healthy caution in his reaction—he has disciplined instincts. By contrast, Macbeth is example of a man of keen but undisciplined instincts who lets his mind be overwhelmed at the prompting of perceived supernatural instruction, leading him to addiction (for blood and power), insomnia, paranoia, and hallucinations.

Shakespeare shows us explicitly how Macbeth's thought process turns a prophecy into direction and then parses direction into a wide range of options and, under his wife's influence, narrows those options to the most extreme single action. He argues with himself, weighing desire, social standing, an ideal of honor, and different means of attaining the promised goal (including, hello! waiting until the crown passes to him without his doing a thing). As surely as we can watch cumulus clouds compound into a severe thunderstorm, we can see Macbeth's brain enweb itself in a sense of logic warped by his interpretation of the supernatural visitation; it's natural sequencing inwards to a skewed brain.

That sequencing, revealed to us in soliloquies and asides, is presented in real time; Macbeth speaks it as he thinks it. This is an important point to remember when King Duncan names Malcolm as immediate heir to the throne. Reacting to this unexpected obstacle that he must overleap, Macbeth says, "Let not light see my black and deep desires." Taken out of context this sounds like he's already intending to murder the king; but note its place in the sequence of his meditations. Duncan has just expressed that his debt to Macbeth is more than he can pay and he will "labor to make thee full of growing"—a promise Macbeth hears shortly after the Weird Sisters' second salutation, that he is Thane of Cawdor, proves true. Macbeth would be predisposed to hearing Duncan pronounce the Weird Sisters' third salutation, that he will be king hereafter, but Duncan instead tabs Malcolm as Prince of Cumberland. It's a splash of cold reality on a hot-festering phantasm of ordained desire. As such, it highlights Macbeth's most primal thoughts. I have never harbored thoughts of murder, but I will admit that in immediate moments of deep disappointment I have had some other primal thoughts lurch into my conscious, and I don't want mine illuminated, either. I then work to squelch my urges. Macbeth tries to work through his, too, but he isn't able to totally dismiss the thought of murdering Duncan. Still, it takes another couple of scenes, more soliloquies, and a hot wife questioning his manhood before he commits to the urge, and even then, he still worries over it.

Such are the psychological forces, a mind at war with itself, that affects Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, Othello, Ophelia, Hamlet, and King Lear. All these characters, at least on the surface, start their plays in healthy states of mind, except perhaps Hamlet, who is in an obvious state of grief and depression. King Lear is old, but that is not the sole pathology affecting his mind. In fact, I am more like Lear than my 85-year-old, stroke-impaired father is. "O, let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven! Keep me in temper: I would not be mad!" Lear laments in a sudden, out-of-nowhere eruption. He knows that his fragile mind is slipping, that what he thought was reality has become something strange to him, and he has somehow ended up on thin ice.

Eric Minton

July 10, 2014

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances