Gallant Youths

Shakespeare Casts a Wary Eye

On Youthful Exuberance

He's a man of action, and we love him for it. He wields his weapon with ferocity and ever displays a tempestuous nobility. He enters the field with such an aggressive desire to triumph it can outrace strategic common sense. Ignoring all obstacles as he chases honor, he runs headlong into figurative fences—and literal ones, too.

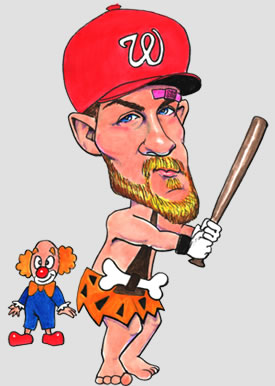

We are, of course, referring to Hotspur—and Harper: Harry of England's Northumberland and Bryce of Washington's Nationals.

Washington, D.C., is currently gripped with controversy, not so much on Capitol Hill and in the chambers of regulatory hubbub but on the diamond and gridiron. There, the trumpet calls of youthful exuberance and millennial attitude announce a new order in the persons of 20-year-old Harper, the slugging outfielder with the Major League Baseball Nationals, and 23-year-old Robert Griffin III (RGIII), the starting quarterback of the National Football League Redskins. Both are in their second years of top-level play after all-star rookie seasons. Both are incredibly talented, obviously intelligent, and, by all accounts and indications, morally upright individuals. Both are also athletic phenomenons who display a maximum play-at-all-cost-all-the-time effort that first bewilders, then inspires, but ultimately bothers their elders. How Shakespearean.

Washington, D.C., is currently gripped with controversy, not so much on Capitol Hill and in the chambers of regulatory hubbub but on the diamond and gridiron. There, the trumpet calls of youthful exuberance and millennial attitude announce a new order in the persons of 20-year-old Harper, the slugging outfielder with the Major League Baseball Nationals, and 23-year-old Robert Griffin III (RGIII), the starting quarterback of the National Football League Redskins. Both are in their second years of top-level play after all-star rookie seasons. Both are incredibly talented, obviously intelligent, and, by all accounts and indications, morally upright individuals. Both are also athletic phenomenons who display a maximum play-at-all-cost-all-the-time effort that first bewilders, then inspires, but ultimately bothers their elders. How Shakespearean.

But these modern characters, when compared to William Shakespeare's creations, shed a little light on the playwright's own attitudes toward youth.

As a season-ticket holder of the Nationals, I am a big fan of Harper. I also happen to adore the character of Henry "Hotspur" Percy in Henry IV, Part One, the brash young lord who goes on a rant about a la-di-da "Popinjay" nobleman, peevishly complains about the king's orders, impishly insults his Welsh host, and foolishly leads an outnumbered army of rebels against the king. Though Hotspur is ultimately a serious character, Shakespeare imbues him with wonderful comic lines and situations. But I never connected Hotspur and Harper until this past weekend when, first, we saw Harper have one of his "he's only 20" moments, and then we watched The Hollow Crown, the series of Shakespeare history plays airing on PBS this month (which I am reviewing for Shakespeareances.com). In the Henry IV, Part One installment, Joe Armstrong's Hotspur not only behaves like the Harper we saw on the field, but looks a little like him, too. It is another example of how Shakespeare drew such a singularly vivid character who nevertheless proves to be universal.

The comparison goes beyond an actor's looks and the impetuous, hyperactive behavior the knight and the Nat share. Hotspur adores his horse, Harper kisses his bat. Despite being cautioned to keep the conspiracy against the king secret, Hotspur carelessly writes a letter to another lord about it. Despite the Nationals urging restraint about loose-cannon statements getting in the press, Harper continues Tweeting controversial commentary. Hotspur stands up to Glendower: when the Welsh lord contends that "I can call spirits from the vasty deep," Hotspur says, "Why, so can I, or so can any man, but will they come when you do call for them?" Harper stands in against pitchers: when one veteran pitcher nailed him with a "welcome to the big leagues, punk" pitch allowing him to take first base, Harper sped to third on the next batter's single, then stole home. With half his forces missing, Hotspur nevertheless engaged the king's forces at Shrewsbury out of a sense of honor and an aggression-is-best strategy. With the Nationals down by nine runs and needing baserunners, Harper nevertheless tried to stretch an easy double into a triple out of a sense of honor and an aggression-is-best strategy. Harper was out at third; Hotspur was killed.

OK, so that's kind of a big difference. Harry Percy was engaged in warfare, Bryce Harper is playing baseball. No matter how many walls Harper runs into or how many times he swings a bat at a wall out of frustration only to have the bat bounce back and hit his own forehead, he is not risking his life in his pursuit of honor. Yet, the comparison is still apt. Shakespeare mentions the occasional sport (including young Laertes in Hamlet and the young Dauphin in Henry V playing tennis), but he doesn't depict any athlete, per se, other than the wrestler in As You Like It. Rather, he depicts the medieval equivalent to team sports: warfare. Most of the characters in the canon who go off to war do so in search of honor, wealth, and superstardom, whether it's the English barons in the history plays or the Bertrams and Macbeths in the comedies and tragedies. Based on Shakespeare's accounts, the general population paid close attention to the feats and failures of individual warriors. I can imagine serf kids trading knights cards, if such a thing existed. True, these characters might go into military service today, but I can imagine Romeo as a point guard, Mercutio as a right winger, Benedick as a relief pitcher, and Petruchio as a NASCAR driver. Prince Hal, of course, would be a couch potato.

No matter the skill set, it's the attitude of youth—specifically, as displayed in public—that Shakespeare is exploring in his depictions. Across the canon, he doesn't concern himself with specific ages unless it really matters. On one end of the scale, Shakespeare will go to great lengths to depict old age, from Falstaff to Lear. On the opposite end are the boys, from the princes in Richard III to the Page in Henry V, the 13-year-old Juliet (not so sure about Romeo's age), and Miranda in The Tempest who, by the math in Prospero's history, is no older than 16. Hamlet is, specifically, 30 years old, and yet he seems to be depicted as about 20 (he's a college student) who acts like he's having a mid-life crisis. While Shakespeare gives Hamlet a specific age, that ageless portrayal is more typical of his characters, men and women. However old you cast any of these characters is an assumption. Even Prospero could be as young as 30 or as old as 70. If you shed yourself of these assumptions—i.e., Juliet's Nurse might be 30 instead of 60, Petruchio might be 50 instead of 30—unlimited possibilities in interpretations emerge. Take Macbeth, for instance. The Macbeths are usually played as middle age-ish. Cast them in their 60s and watch how their motivation to kill the king shifts. Now, cast them as 20-somethings, and you get an entirely different reading of the play.

The history plays would seem to give directors some parameters to work with, but Shakespeare mucks it up. Richard II was 33 when he was deposed, Richard III was 32 when he was killed, but if you've seen or read both plays, who would you consider older?

In Henry IV, Part One, Shakespeare wields his thematic hand specifically in depicting youth. The real Hotspur was 39 years old, three years older than King Henry IV. Prince Hal was two months shy of his 17th birthday. But Shakespeare wanted to juxtapose Hotspur and Hal, so he makes them peers. He does not state an age for either, but clearly depicts them as young, or at least his idea of young: the wayward, party-hard prince versus the rash, brash, honor-seeking rebel. In other plays Shakespeare uses similar attributes to portray young men and women, namely Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Titus Andronicus. Mercutio could well be in his 30s and Romeo 24, but Shakespeare leaves no doubt by their behavior (vis a vis his depiction of Hal and Hotspur in Henry IV) that they are maybe 20 and probably 16. Tamora's whelps in Titus are bored teens who indulge in wilding, and the four lovers in Dream don't have the worldly wisdom to be over 18.

Whether this was Shakespeare's own opinion of young people, we'll never know, but he at least was playing off the accepted assumptions of his audience. That goes into why people roll their eyes today whenever Bryce Harper slams his helmet down on the ground after he hits a groundball out. That factors into why people raise eyebrows when RGIII publicly questions his coach on the status of his knee injury. Well, Harper is only 20 and RGIII is only 23, people say, and you can't expect them to act much older than they are. But, in fact, we do: they are Major League and NFL stars, so we automatically think they should act our age, not theirs.

Shakespeare, as always, takes the long view. Hotspur does not survive past Henry IV, Part One, and notably, when Hal fatally stabs Hotspur in the battle of Shrewsbury, Hotspur says, "O, Harry, thou has robbed me of my youth." Would Hotspur have outgrown his immaturity had he not been so robbed? Hal certainly does: 10 years later in real time (two plays later in Shakespeare time) he becomes the great Henry V.

We should then judge Harper and RGIII not so much in the moment but in the continuum of their chronology. Many pundits are loath to label Harper and RGIII as "immature," instead presenting the mathematics that one is "only 20" and the other "just out of college." Yet, both are already playing at a level Hall of Famers didn't attain until their mid- to late 20s. The Hotspur of Shakespeare's play may act his age, but his feats before Shrewsbury brought him acclaim through three nations, and Shakespeare never lets us forget that.

Eric Minton

September 6, 2013

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances