A Midsummer Night’s Dream

T'expound on a Dream with Most Rare Vision

Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Sunday, November 3, 2013, D-101&102, front corner of deep thrust theater

Directed by Julie Taymor

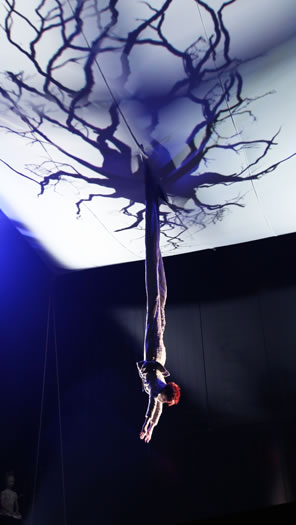

Kathryn Hunter as Puck enters for her first lines in the Theatre For a New Audience's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. The Julie Taymor-directed play opens the TFANA's new theater at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Brooklyn. Photo by Es Devlin, Theatre for a New Audience.

If it's hallucination you need to portray, you can find no more adept person to present it in a visual medium than Julie Taymor. Arguably the most visionary of directors—and I'm using visionary in both a physical sense of what the eye sees as well as a psychological sense of what the soul yearns for—Taymor has an enviable track record of taking something entirely mental and recreating it as a stage play, from the supernatural visions of The Tempest to the comic book fantasy world of Spider-Man, from the Disney land of talking animals in The Lion King to Shakespeare's nightmarish sequence of events in Titus Andronicus.

"I have had a most rare vision," Bottom says in William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. "I have had a dream past the wit of man to say what dream it was." The weaver then says he will get Peter Quince to write a ballad of the dream, but if he went straight to Taymor she would find a way to stage the dream itself. And so she does, in dreamlike fashion, for the grand opening of Theatre for a New Audience's new home, the Polonsky Shakespeare Center.

After 34 years as an itinerant but highly successful New York theater company, TFANA has taken up permanent residence in a new structure adjacent to BAM in Brooklyn. The $65.1 million capital campaign received $34.4 million from the City of New York through the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the Office of the Brooklyn Borough President; the Polonsky Foundation provided a $10 million gift; and the Samuel H. Scripps Foundation, for which the 299-seat mainstage playing space is named, gave $5 million (the campaign still needs to raise $3.6 million).

If you want to show off your fancy new playing space, Taymor is the director of choice, beyond the fact that she has previously staged The Tempest, The Taming of the Shrew, Titus Andronicus and Carol Gozzi's The Green Bird for TFANA. The design team of H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture LLC, Theatre Projects Consultants, and Akustiks has created a flexible courtyard-style theater (configured in deep thrust stage for this production) with a myriad of rigging and backstage options. (The acoustics are outstanding, but with our seats at stage level, we had some sightline issues in some scenes). Taymor uses every toy provided by the design team in order to carry out her dream of a Dream. She flies people and furniture. She transforms a giant, white, bed sheet into a sky of billowing clouds and then makes it a canvas for graphic doodling. She uses the stage's many trapdoors for subterranean moments, for practical stage magic, and as the gallery for the royal court to use when watching Pyramus and Thisbe. She manipulates the back wall to create varying levels of action.

The production opens with Puck (Kathryn Hunter, looking like a cross between Chuckie and a carnival barker) climbing into a bed that is then pushed up to the ceiling by a tangle of trees. As the bed carrying Puck flies out of sight, its bed sheet becomes the sky. When Puck makes her first proper appearance at the start of act two, scene one, Hunter lowers head first through the sheet ceiling, her legs extending the whole way as a pen-and-ink drawing of roots expands on the sheet. The play's first half ends with Titania (the majestically sensual Tina Benko), legs spread, being raised up in her bower to the back wall, and Bottom (Max Casella) sitting in a moss-covered easy chair being pushed into a sheet that envelopes him and sucks him through the back wall below the climaxing Titania. If that sexual imagery is not obvious enough, bower and all turn into a screen showing a sequence of blooming flowers that get bigger and bigger until we feel we are about to be swallowed up in their gynoecia.

Notably, these are not special effects: rather, they are obvious theatrical effects. We see the cables flying Puck and Titania, we see the ropes manipulating the bed sheet, and we see the rude mechanicals themselves doing all the work—they not only produce Pyramus and Thisbe for Theseus and his court, they produce A Midsummer Night's Dream for us (only much more professionally). Children play what Taymor calls the rude elementals, not only the fairies but elements of the woods, from snakes to deer to the fiends chasing the rude mechanicals after Bottom's transformation (though Taymor is possibly the world's most renowned puppet designer, she keeps puppetry to a minimum in this production). The woods themselves are the children carrying bamboo poles shifting around the stage as the four lovers make their way through brambles and branches.

With a seeming cast of thousands (actually, 36), the production seems to owe much to Max Reinhardt, whose grand-scale production was turned into the 1935 Warner Brothers movie. Taymor differs in two significant ways: in intimacy and in fealty to the play's language, getting to the roots of the varying types of love Shakespeare portrays and how humans can behave so barbaric (Theseus reportedly toward Hippolyta, Egeus toward his daughter Hermia) while spirits "of no common rate" can behave so human (Titania toward Bottom, Oberon toward Titania). She's assembled a strong cast with solid verse-speaking abilities and relies on the actors' particular physical attributes to enhance their characters' portrayals.

Hunter's contortionist abilities and eye-twinkling expression, even when Oberon is berating her, create an impish Puck who simultaneously intrigues us and creeps us out. Benko just has to stand still and her Titania exudes sexuality. David Harewood seems larger, more muscular, and much darker (with a blue tone, even) as Oberon than he does as David Estes on the Showtime series Homeland. You feel he could wrap you in the most loving of bear hugs or snap you like a bamboo twig as the glow emanating from him swings warm and cool. Costume designer Constance Hoffman, who uses a timeless fairy tale aesthete for the Athenian court, dresses the Fairy Queen in a classic European prom gown with glowing sheer train while the King of Shadows wears harem pants and an ornamental halter that looks like a ring of twigs, something an ancient African king might wear. Both have wings that remain folded on their back until they are angry; instead of hissing at each other they rattle their wings.

Zach Appelman, a young actor on his way to rarefied Shakespearean heights, is the lynchpin lover as Demetrius, his chiseled good looks and ramrod straight demeanor making him the Clark Kent any father would want for his Hermia. But in Lilly Englert's tempestuously impassioned portrayal, this Hermia clearly prefers the poetic, long-haired rebel Lysander, played by Jake Horowitz (son of TFANA Founding Artistic Director Jeffrey Horowitz) with barely bounded enthusiastic energy. Mandi Masden is a prim and proper Helena whose sense of self is only what she sees in others' reflections of her; it's not an engaging characterization, but is no less appropriate for being so.

If this production has anything to slight, it's the way the lovers end up in their underwear by the end of their brawl in the woods. The stripping down comes across as an obligation to tradition rather than germane to the action, especially as the action is a tad antiseptic, These particular personalities established through the foursomes' performances don't seem inclined to unbridle their passions in a strip-down throw-down, and though moving about in boxer shorts and slips, they just don't seem able to cross the line into wild abandon.

The actors playing the rude mechanicals, on the other hand, let loose with indelible performances. This is the most disparate "crew of patches" you are likely to find gathering to put on a play, led by Casella as Bottom, the construction site know-it-all who would be the kind to hold court on his brush-with-fame exploits while eating lunch on the girders. Joe Grifasi is the put-upon Peter Quince, William Youmans is the quite-gay tailor Robin Starveling, Brendan Averett is a giant of an electrician as Snug, Jacob Ming-Trent is the no-nonsense painter Tom Snout, and Zachary Infante is the out-of-place Francis Flute yearning for acceptance among his peers (not sure from his camouflage outfit what trade he plies).

Nick Bottom (Max Casella, center) shows his fellow actors how he would play the lion in TFANA's A Midsummer Night's Dream.. From left, Jacob Ming-Trent as Tom Snout, Zachary Infante as Francis Flute, Brendan Averett as Snug, and William Youmans as Robin Starveling. Photo by Gerry Goodstein, Theatre for a New Audience.

These all-pro actors develop distinct character attributes that create many a golden moment in their scenes. Starveling is quick with his tape measure as soon as an actor is given his part, and his "whatever" response to the heckling he receives during his presentation of Moonshine rebounds on the Athenian lords and ladies—his posture and look clearly say, "this is my representation of Moonshine and that's all that counts to me." Flute uses his moment to play Thisbe as his big chance at fame, and he pours his very essence into Thisbe's death, creating the production's most powerful moment (and by production I mean A Midsummer Night's Dream, not just Pyramus and Thisbe). Averett's Snug gets carried away playing lion, and given his size and big-Bosox-bearded countenance, he truly frightens the ladies, causing the rest of the crew to corral him for fear they will all be hanged.

Ming-Trent delivers the night's funniest line, and it is only partially Shakespearean: When Quince points out that their story requires a wall, Snout, who has been drinking beer and sitting in that mossy easy chair, jumps up and with such common-sense incredulity says "Jesus Christ, you can never bring in a wall!" (the blasphemous interjection is not in Taymor's production script, by the way). Of course, the answer to how you bring in a wall is that Snout himself will play Wall. The rude mechanicals demonstrate that you need never say never when it comes to theater. You can create a wall in an empty space in the time it takes for someone to walk into that empty space; you can make moon shine inside a chamber; and you can turn a person into a realistic lion.

Which, come to think of it, Taymor has done quite successfully herself, too.

Eric Minton

November 8, 2103

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances