Hamlet

O'erstepping the Modesty of Nature

Shakespeare Theatre Company, Sidney Harman Hall, Washington, D.C.

Monday, January 22, 2018, N–2&4 (orchestra center right)

Directed by Michael Kahn

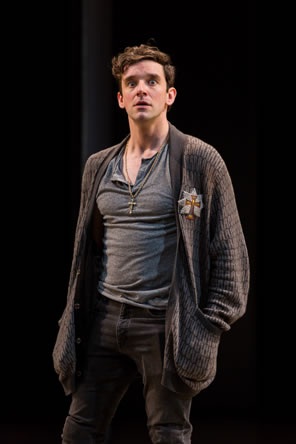

"This was your husband," says Hamlet (Michael Urie) showing his mother, Gertrude (Madeleine Potter) a picture of Hamlet Sr. in the Shakespeare Theatre Company's production of William Shakespeare's Hamlet. Below, Urie's caffeinated portrayal of Hamlet. Photos by Scott Suchman, Shakespeare Theatre Company.

Defining accomplishment can be problematic when it comes to staging William Shakespeare plays. Michael Kahn's attention-to-details direction accomplishes a viable modern setting for the Shakespeare Theatre Company's production of Hamlet at Sidney Harman Hall. Michael Urie accomplishes a high-octane and freshly funny portrayal of the title character. And the whole receives a fervent standing ovation on opening night.

By those same measures, this production falters mightily. That attention-to-details modernizing generates big laughs when the Ghost appears, when Polonius dies, and during the climactic duel. Urie's portrayal of Hamlet violates the very standards Hamlet himself sets as ideal stagecraft. As for that standing ovation, I can't help wondering how much incubated Washington, D.C., audiences rely mostly on reputation, exhibitionism, and cleverness for cleverness's sake in their assessment of quality theater. This is the third Hamlet I've seen in 10 days over a geographical swath of more than 1,000 miles. Though Miami Shakespeare has a fraction of a percentage of the budget the Shakespeare Theatre Company (STC) has, and the American Shakespeare Center version I saw in Staunton, Virginia, was a preopening run-through after just one week of rehearsal, on the sole criteria of substance—i.e., "caviar to the general"—the comparative ovation for those two productions would be a roar to blast off the Sidney Harman Hall roof.

Kahn, heading toward his last season as STC's artistic director, has gathered an impressive cast of talent for this his third time helming Hamlet, but the actors seem to be performing in their own isolated tracks. That's how pop music and movies are put together these days, but in live theater it lacks the congruity of a good mix. Actors' truly listening was a missing quality of the opening night performance, except, of course, when characters were engaging in surveillance (Claudius and Polonius use a microphone hidden in the book Ophelia carries to eavesdrop on her encounter with Hamlet in the nunnery scene). Sometimes they don't even listen to themselves. Polonius in Robert Joy's portrayal is officious but efficient in manner, but his precepts to Laertes (Paul Cooper) come off as doddering stuff, at least to Laertes and Ophelia (Oyin Oladejo). This counselor as otherwise portrayed would be the kind to put his arm around his son and coach him in these hackneyed, perhaps, but yet serious truisms for maneuvering through the world with a keen sense of diplomacy—something Polonius himself has much skill in.

In modern dress (Jess Goldstein, costume designer) on Scenic Designer John Coyne's sparse stage resembling the lobby of a federal agency, with angular pillars and sheet flooring plus metal balconies to one side and across the back, Kahn aims for a sense of present political ubiquity. "While I was thinking about this play over the past year and a half, the world changed," Kahn writes in his director's notes. "It's not just happening here in the United States, but all over the world—people are seeking power in strongmen. There is the serious possibility of a return to autocratic governments in a manner that seemed inconceivable just a few years ago." And with such autocracy comes a "kind of paranoid surveillance state," Kahn writes. "This is a play where everybody spies on everyone else, a society where trust is meaningless, in large part because there is a cover-up going on of a very serious crime that has been committed." Even pretending to be insane, Kahn says, is a means for the spied-upon to become a spy himself.

This "poisonous atmosphere" makes not only Denmark a prison for Hamlet but his own mind a prison, too. Urie, a critical darling for, among other recent New York outings, his performance in Jonathan Tolins' Buyer and Cellar and a persistent television presence since his role as Marc St. James on Ugly Betty, opens this production with Hamlet's first soliloquy, "O, that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!" (the speech transferred here from the middle of the second scene in the text). By the soliloquy's third line, Urie's emoting has dialed up to 11; he must have downed five venti espressos with a 5-hour Energy chaser before walking onto the stage. He puts on a frantic disposition from the start, ceasing only when poison quite o'er-crows his spirit at the end of the play and we can blink again. He saws the air with his hands as he tears a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings, who Urie perhaps believes are for the most part capable of nothing but inexplicable dumb shows and noise. Yes, I'm quoting directly from Hamlet himself in his advice to the players. The way Urie's Hamlet decries actors who saw the air with their hands while demonstrating sawing the air with his hands in the exact same way Urie saws the air with his hands throughout the entire play could be the ultimate ironic humor: for "Anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing."

Or it could be Hamlet truly holding a mirror up to nature—Urie's nature, at least. At the end of his tête-à-tête with Polonius, who departs with "I will most humbly take my leave of you," Hamlet replies, "You cannot, sir, take from me any thing that I will more willingly part withal: except my life, except my life, except my life." By the third repetition of that phrase, Urie's Hamlet is bellowing and pointing a pistol in the direction of Polonius's exit. He then turns the pistol on his forehead and moves directly into "To be or not to be" (another repositioned soliloquy), slashing through the passage and displacing its psychological eloquence with a sound and fury signifying he's really hurting, man.

Urie does achieve a singularly powerful moment during Hamlet's confrontation with his mother after he accidentally kills Polonius. He forces Gertrude (Madeleine Potter) to compare the images of her first and second husbands, Hamlet's father and Claudius, respectively. As Hamlet holds high above his head a handbill of the elder Hamlet he keeps folded in his pocket, he praises the man with a heartfelt passion that comes from growing up in idolatry of a father formed by all the best aspects of the gods who is suddenly snatched away. This is not "seems" or the trappings of woe. Hamlet then shows Gertrude a photo of Claudius on his mobile phone (apparently the one he snapped at the climactic conclusion of the Mousetrap). Giggles start rippling through the audience even before he says, "Here is your husband, like a mildewed ear." The riveting, pivotal emotional point in Urie's portrayal of Hamlet is deleted in a texting-based laugh more than a textual one.

Hamlet is a funny play. It is full of jokes, puns, and comic situations, not to mention the bona fide comic characters of the gravedigger and Osric. "Stoppardizing" Rosencrantz (Ryan Spahn) and Guildenstern (Kelsey Rainwater) also raises the play's comedy quotient, as it does in this production (they receive the wrong nametags when they are admitted to the king's and queen's private quarters). Hamlet himself is one of Shakespeare's great comic creations, revealed, as we've seen before as well as here, in having a comic actor play the part. The question, though, is whether the audience is laughing at the play or at the production—not at the production's quality, per se (though the guffaws following Urie's flippant farewell as Polonius falls dead might have been unintended), but rather at the extent of Kahn's updating the play's setting.

Take the opening scene—er, the second scene in this production—when the ghost appears on the rampart. It is set in a security office, a bank of six screens over the operations desk. Francisco (Brayden Simpson) buzzes in Bernardo (Chris Genebach) arriving for his shift carrying a tray of three coffee cups. They buzz in Marcellus (Glymph) and Horatio (Federico Rodriguez). The screens go blank and the Ghost (Keith Baxter) appears on one of them. Horatio addresses the Ghost through the intercom. Each of these bits—even the arrival of the coffee—gets a laugh, as if making Shakespeare modern is cute. More importantly, these bits remove the specter of fear of the specter, including in the subsequent scene as the Ghost appears in person on stage to Hamlet.

Hamlet texts his love messages to Ophelia; nothing wrong with that, but the audience titters. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern take a selfie on the king's couch before Claudius enters: that is such an R&G thing to do and deserves its laugh. The climactic duel between the ever-dower Laertes and the ever-frantic Hamlet is contested as épée with electronic signals: this has promise as just 10 days before I saw one of the most scintillating stage combat events ever in Hamlet's and Laertes' 1920s set fencing duel. However, the fencing in this production is sloppy (snickers) and stops for slow-motion replays on monitors above the arena (LOLs galore). Meanwhile the escalation of violence lacks personality.

Out of the production's hyperkinetic soullessness arise three superb portrayals. Alan Cox is the scariest Claudius I've ever seen precisely because the king we watch in the first half doesn't match the Claudius we know from seeing or reading this play umpteen times. First-timers watching this production would think the Ghost is lying, given how Cox plays Claudius with bedeviling charm, statesman's efficiency, natural joviality, and genuine affection for Gertrude, Hamlet, and the Polonius family. We learn the truth about him at the same moment Horatio does, via his reaction in the Mousetrap: perfect (even though Shakespeare earlier gives Claudius an aside admitting his guilt; that's Shakespeare's mistake, and this and most productions wisely excise that aside). Only after that, especially when he oversees the torture of Hamlet, does Cox's Claudius reveal his despotic ways.

Out of the production's hyperkinetic soullessness arise three superb portrayals. Alan Cox is the scariest Claudius I've ever seen precisely because the king we watch in the first half doesn't match the Claudius we know from seeing or reading this play umpteen times. First-timers watching this production would think the Ghost is lying, given how Cox plays Claudius with bedeviling charm, statesman's efficiency, natural joviality, and genuine affection for Gertrude, Hamlet, and the Polonius family. We learn the truth about him at the same moment Horatio does, via his reaction in the Mousetrap: perfect (even though Shakespeare earlier gives Claudius an aside admitting his guilt; that's Shakespeare's mistake, and this and most productions wisely excise that aside). Only after that, especially when he oversees the torture of Hamlet, does Cox's Claudius reveal his despotic ways.

Potter's Gertrude is surprised at her husband's response to the Mousetrap, but she's already peeved at the obvious references to her in the play Hamlet has chosen to show for the court. Potter plays Gertrude as a woman with bred fortitude, perhaps not romantically inclined toward Claudius but affectionate enough to appreciate the opportunity to maintain her role as queen. She takes a no-nonsense approach to everybody—Hamlet, Polonius, even in her kind words to Ophelia. Hewing to Shakespeare's rather illogical progression of lines in the closet scene doesn't undermine this choice of portrayal, for Potter reveals a mother overwhelmed by a barrage of horrors (Polonius slain, Hamlet seeing ghosts), sad memories (Hamlet's adulation of her first husband reminding her of her own lost love), and insults (Hamlet's pointed remark that she's too old to enjoy sex) hitting her in the space of five minutes. Potter's behavior at the end also indicates she suspects the cup—intended for Hamlet—is poisoned: it's a brief moment that freezes audience laughter into chilled spines.

Another moment of pause likewise lifts this rendition of Hamlet above all its trappings of whoa! It comes when the Ghost appears to Hamlet in Gertrude's closet, but she doesn't see the specter. Over the centuries critics have questioned Shakespeare's inconsistency in portraying the Ghost, whom the guards and Horatio can see along with Hamlet, but Gertrude can't. Baxter's Ghost is equally puzzled; he's come to whet Hamlet's purpose, but he also wants to comfort his wife ("O, step between her and her fighting soul," he implores Hamlet). With the realization that she can't see him comes horrible disappointment for the Ghost, and Baxter turns dejectedly and "steals away."

Some other moments bear reporting.

- Hamlet can hear Polonius's asides: that might seem to be breaking convention within the play (nobody can hear Hamlet's asides), but it serves as social commentary for how we treat people with mental disabilities.

- The speech of "some dozen or 16 lines" that Hamlet sets down for the players is in this production the murderer's speech, ultimately interrupted by Hamlet, in the Mousetrap.

- The production's first half ends with security forces killing the Player King under Claudius's watchful eye: extra-textual superfluity.

- The last image of the production comes after Fortinbras speaks the denouement as on the screens above we see Lenin's statue being pulled down: some in the audience chuckled knowingly, but I'm not sure what the image is meant to accomplish.

For me, a theatrical highlight is Baxter as the Player King (he plays the Gravedigger, too) delivering the Christopher Marlowe–inspired speech about Priam and Hecuba. As he speaks of Priam, Baxter is ever moving, hopping on the balls of his feet, and gesturing the action of which he speaks, a visually busy presentation with slapstick tones. Polonius cuts him off complaining, "This is too long." Hamlet instructs the Player to continue, to "come to Hecuba." While delivering the second half of the speech, Baxter's Player remains still as the tragedy described in the verses, despite their archaic formality, well up inside of him. The performance overwhelms Polonius, awes Hamlet (the self-styled acting aficionado), and strikes the theater audience into pin-drop silence—quite the accomplishment.

Eric Minton

January 24, 2018

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances