Hamlet

Good Radio vs. Good Shakespeare:

With This Hamlet It's a Drawl

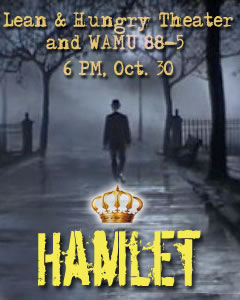

Lean & Hungry Theater, WAMU 88.5 FM Radio, Washington, D.C.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Directed by Kevin Finkelstein

This was my first experience merely listening to a Shakespeare play (albeit, trimmed to one hour of broadcast time). I quickly realized that unlike listening to old radio programs like The Shadow and Jack Benny where I created my own visuals, with Hamlet I borrowed my visuals from every Hamlet I’ve seen, even though this one is set in antebellum South Carolina.

This was my first experience merely listening to a Shakespeare play (albeit, trimmed to one hour of broadcast time). I quickly realized that unlike listening to old radio programs like The Shadow and Jack Benny where I created my own visuals, with Hamlet I borrowed my visuals from every Hamlet I’ve seen, even though this one is set in antebellum South Carolina.

So, I perforce will treat this as a stage play, discussing its merits of interpretation, and that may be unfair to the production. In time, I’ll adjust my perspective to the medium, but this production suffers the fate of having its medium adjusted to my perspective. For, as radio theater, Lean & Hungry’s Hamlet has strong production values and professional performances, and it makes a concerted effort to create a singularly audio experience. As Shakespeare, it worked itself into a corner with the choices it made to be that singular audio experience.

One such choice was the framework: A group of people somewhere in the British Isles, based on their accents, are telling ghost stories when Rosencrantz (Brandon Rice) and Guildenstern (Azania Dungee) offer to recount the story of Hamlet, prince of the Elsinore Plantation in Denmark, S.C. At this point, all of you Shakespeare buffs will be either very intrigued or very afraid. So let’s establish that if you like mashing your Shakespeare into a new form (but keeping the verse), this is for you; if you like your Shakespeare pure, start trembling.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were not ghosts (one of the Brits actually asked that) and this device borrowed nothing from Tom Stoppard. They were slaves at Elsinore, assigned to watch Hamlet and then accompany him to England. But rather than send them to their deaths, Hamlet’s rewritten letter freed the slaves in his benevolence, and then upon his return to Denmark, he gave out that they were dead. Horatio (Patricia Dugueye) was a former slave, one so intelligent she accompanied Hamlet to school at Wittenberg and received an education herself. The slave motif came into sharp focus in the frequent “your servant ever” lines the three speak, and it at least provided a foundation for accepting the play's awkward friendship between Hamlet and Horatio.

Rather than treating the antebellum South as an allegorical setting for a play about a Danish king’s cat-and-mouse game with his nephew and true heir to the throne, Lean & Hungry made the setting specific via the non-Shakespeare lines of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s narration. Thus, while the whole Fortenbras subplot was dropped, there remained awkward references to king, prince, and “my lord.” The setting was intriguing, however, and apt as I imagined watching Hamlet speaking “To be or not to be” while riding his horse through the tree-lined avenue leading up to Magnolia Plantation outside Charleston and coming upon Ophelia (Shannon Listol) in a hoop skirt and frills, as I listened to Gertrude's (Barbara Papendorp) Mrs. Gump-like fawning over her son, and as I heard Alex Zavistovich double as the Ghost, speaking like a Calhounian lion of the Old South, and Claudius, sounding more like Boss Hogg (interestingly, Michael Harris as Hamlet talked more like this production’s Claudius than his father).

The Southern accents, especially Hamlet’s, were so thick you could cut them and spread them on bread. Coming from Southern stock myself, I don’t have a problem with molasses Shakespeare, but though Harris hewed to the verse structure, his drawn-out drawl almost masked his verse-speaking skill, and what was left of his soliloquies after trimming seemed to suffer a sense of randomness while his tone was incessantly whining. On the other hand, Paul McLane not only maintained his verse structure but focused more on the poetical rhythms Shakespeare imbued them with; not surprisingly then, his Polonius emerged as this production’s most interesting, fully developed character.

Yet, like most Shakespeareances, Lean & Hungry’s Hamlet opened my ears to an aspect of the play I had not grasped before. That came in the nunnery scene, a moment in the play I’ve long been ambivalent about: Is Hamlet toying with Ophelia, is he truly mad here, is he simply manic, or is he realizing a trap has been laid? In Harris’s baleful tone and the line cuts putting more focus on the lines that remained—key among them “I am myself indifferent honest, but yet I could accuse me of such things that it were better my mother had not borne me”—I heard this tirade of Hamlet’s as a lament. Juxtaposed as it is with his “To be” speech, it escalates the play's existential theme from one of an individual’s will to live to questioning the merit of all mankind’s continuing existence.

Ultimately, what makes Hamlet both so brilliant and so hard to produce is that Shakespeare has written not only a great ghost story and political thriller, he also has drawn a character that mines the deepest fathoms of our metaphysical being. It's Jerry Bruckheimer mashed with Ingmar Bergman in one seamless whole. Hamlet’s greatness is its whole not the sum of its parts. When you excise too much matter and alter its plot points you have something no more memorable than all the Hamlet tales dating back to the 12th century on which Shakespeare based his play.

Eric Minton

November 19, 2011

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom