1984

Stepping through Orwell to Our World

By George Orwell, adapted by Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan

Headlong, Nottingham Playhouse, Almeida Theatre, Shakespeare Theatre Company, Lansburgh Theatre, Washington, D.C.

Monday, March 21, 2016, E–118 (left stalls)

Directed by Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan

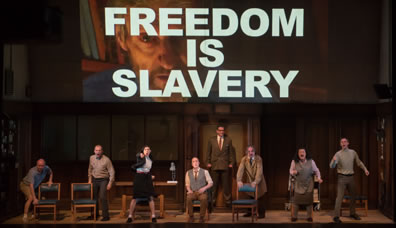

Members of the cast of Headlong's 1984 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company engage in "Two Minutes Hate," yelling at the image of Brotherhood leader Goldstein on the video screen above the stage, except Winston (Matthew Spencer) sitting in the middle, and O'Brien (Tim Dutton) standing behind him. From left are Parsons (Simon Coates), Martin (Christopher Patrick Nolan), Julia (Hara Yannas), Winston, Charrington (Stephen Fewell), Mrs. Parson (Mandi Symonds), and Sym (Ben Porter). Photo by Ben Gibb, Shakespeare Theatre Company.

Leaving the Lansburgh Theatre after watching this explosively powerful, extraordinarily acted Headlong production of George Orwell's 1984, I couldn't shake the realization of how naive I had been earlier that day. Giving an oral history of a government commission I have just finished working with, and noting how the commissioners were unified in their findings and recommendations—not a single dissenting opinion in their final report—I opined that truth is the truth. We may all have different opinions on policy, trends, and potential outcomes, but when presented with clear facts and thoroughly researched data of past and present circumstances, the truth is obvious.

But in the novel and play 1984, and in the real 2016, there are truths and there are facts, and, in some quarters, never the twain shall meet. That the Shakespeare Theatre Company is hosting Headlong's touring production of 1984 in the middle of what is arguably the most bizarre presidential election campaign in our nation's history is a revealing circumstance. In this production—first staged at Nottingham Playhouse in 2013 and continuing on in various residencies in London (the Almeida Theatre along with Nottingham Playhouse are co-producers with Headlong) plus UK and international tours—adaptors and directors Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan use live video to heighten the omnipresent sense of surveillance in Orwell's story (i.e., Big Brother). Pointed directing and superb acting create a pervasive paranoia that clutches at our breasts in the audience. In these post–Edward Snowden times, Big Brother watching us and pervading paranoia are obviously relevant.

However, it's the play's exploration of the shifting foundation of truth and historical record that strikes the most discomforting chord for me. That, in fact, is the play's primary intent based on the framework Icke and Macmillan use to tell the story of Winston Smith, 1984's protagonist, who clumsily attempts to rebel against the Big Brother government of Oceana. It's a framework Orwell himself used in the original novel, but most of us who read the book in high school or college ignored.

Orwell included a footnote just a few pages into his novel and an appendix after "the end." Both academically describe the tenets of Newspeak, Big Brother's attempts at paring the English language down to its simplest elements: for example, instead of having an antonym for good, such as bad, you just add "un" to the word, ungood. "Newspeak is the only language in the world whose vocabulary gets smaller every year," says Syme in the play. "It's a beautiful thing, the destruction of words." While everybody else in the audience is laughing, this writer is shuddering—and not from any fear over the long-term impact texting and Twitter might have on our language: I'm more concerned with the short-term impact on our #IndependentThinking.

In the novel, both the footnote and appendix are written in the past tense. The appendix also ends with 2050. Furthermore, the appendix mentions Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, and Dickens, historical figures Big Brother would have unpeopled. It also mentions Winston Smith; if this were Orwell's appendix, including his novel's protagonist might make sense, but the appendix has a fictional signature. Orwell is clearly continuing the novel with the appendix and, writing in 1948, set it further in the future than the 1984 timeframe of Winston's story, some time after Big Brother must have been toppled and the nation of Oceana ceased to exist. This casts the 1984 story itself into a different perspective, for Winston apparently was not unpeopled, and his diary survives to be read by the unborn, something he hoped for but was certain would never happen.

"According to the Orwell Estate, ours is the first attempt to dramatize the appendix in any medium," Icke and Macmillan write in the foreword to their script. "It never felt less than 'essential': given the novel's interest in records and documents and their relationship to truth, the appendix perfectly complicates the novel that precedes it." They dramatize the appendix by incorporating a book club into the opening scenes as Winston begins writing in his diary. The members of the book club are in modern dress; Winston and the figures from the novel are costumed in a style more 1948 than 1984, though the fashion for the British proletariat did not change much over that time (Chloe Lamford is the production's designer, setting the action in a bureaucracy common room with a hallway behind a row of windows at the back wall).

"Treating Orwell's appendix as 'essential,'" Icke and Macmillan continue, "makes his novel something far more subjective and complex than simply a bleak futuristic dystopia: at the final moment, it daringly opens up the novel's form and reflects its central questions back to the reader. Can you trust evidence? How do you ever know what's really true? And when and where are you, the reader, right now?" Lights flickering off and on; video (on a screen above the stage) organically integrated into the stage action; actors suddenly appearing and disappearing and appearing again as different characters; scenes merging, overlapping, and crossing time; the ongoing war we keep hearing about in either the book's time or the future time—or both: it's all brilliantly disorienting. "Where do you think you are?" Winston is constantly asked; we can't answer, either—for him, or for ourselves.

It all sounds Matrix-like, but we're talking 1984, a book that has been a part of our culture's collective subconscious since the moment it was published in 1949. Most audiences no doubt attend expecting to experience Big Brother's omnipresence and the depressing consequences of such totalitarian behavior, especially the paranoia that comes with knowing your every move is being watched. You get this in the director's use of startling noises (Sound Designer Tom Gibbons turns noise into an effective crowd-control weapon), the actors shifting from character to character, and characters shifting from purpose to purpose, and the video showing live feeds from the stage. All the action in the hideaway room where Winston and Julia carry out their affair is presented entirely on the video screen—and you are certain it's all filmed ahead of time and the actors are enjoying a much-needed break in this play's intense, 1:45, no-intermission running time. However, at the point of Winston's arrest, the set dissipates, and we see that room backstage; aside from undermining our own confidence, we are reminded how public our own private lives may be.

The play also reminds us what a potboiler of a thriller Orwell wrote. When, and how, will Big Brother strike? (The inevitability is essential to the suspense.) Who can you trust? Who can't you trust? Even as you are leaving the theater you can't be sure—not just Julia, but even Winston may not have been who he seemed. Icke and Macmillan further heighten the suspense by inserting such things as sudden vocal eruptions, long pauses in the dialogue, and off-kilter timing, all of which the cast executes with precision.

The actors contribute to the tension through a variety of performance styles and techniques for their characters. Stephen Fewell is smoothly sophisticated as the book-club host, nervously genial as Charington the shopkeeper, lobotomized as the canteen cleaner, and full of bwa-ha-ha-ha venom as the thoughtpolice chief. Similarly, Hara Yannas uses a variety of styles to portray Julia over the course of her character's play-long arc, starting with stiff, Nazi-like mannerisms, moving to impatient efficiency as she and Winston have their first sexual encounter, and ending with mothering tenderness as their affair and involvement in the opposition movement of the Brotherhood deepen. On the other hand, Tim Dutton as O'Brien never wavers from his formal, propaganda poster–like presence, whether he is representing the Brotherhood or Big Brother itself. In his performance, we are left to wonder not if the Brotherhood really existed (early on Winston questions whether Big Brother made up the Brotherhood and the war as part of its propaganda efforts) but if Big Brother and the Brotherhood are flip sides of the same coin.

The centerpiece performance is that of Matthew Spencer as Winston, on stage (or screen) for almost the entire play. He remains the skittish, socially awkward, bordering-on-bewildered man (not only conscious of Big Brother's presence in every facet of his life, but also of the unborn people reading his diary somewhere in the future) even as he courageously determines to fight the Party. For two-thirds of the play, Spencer physically portrays Winston's psychological fracturing: the fears, earnestness, confusion, and certainty all roiling in his brain. It's an exhausting performance—and this is before his arrest and time spent in Room 101 where we see him tortured. By the curtain call, Spencer is spent and soaked in blood, which he courteously wipes off his hand before offering it to Yannas for their curtain call bow (he's not quite out of character yet). Meanwhile, on his other side, Dutton just grabs Spencer's hand, as if getting all that blood, sweat, and tears on his own hand is worth the honor of sharing a bow with an actor who has just given his all to his art, and brilliantly, too.

We are spent, too. So emotionally raw and psychologically disturbing is this piece. Nevertheless, as the audience appreciates Spencer with applause, I hope it also is appreciating what Winston has tried to do—reach us, the unborn, through his diary. With 1984 and his earlier novel, Animal Farm in 1945, Orwell was attacking not communism but the totalitarianism that inevitably comes with a government built around communism. In its purist form, Marxist theory is an attractive ideal; long before Marx developed it, William Shakespeare had "the good old lord Gonzalo" describe a communist society in The Tempest. However, the theory can't get past two fundamental truths to achieve large-scale application: one, as a survival instinct, man is naturally inclined to be greedy; and two, man also uses intelligence and creativity—independent thought—to survive. Totalitarian communist governments must corral both greed and independent thought but, due to man's very nature, the totalitarians themselves won't abide by the communist ideals they force on their populations. Orwell saw it happen—thought police and altering historic records, included—in Stalin's Soviet Union. We've seen it in Mao's China, we're seeing it in North Korea. In Animal Farm, the animals lead a worker's revolt, only to see its leaders, the pigs, install a new totalitarian regime and start acting like the humans they overthrew; the cycle continues.

Winston (Matthew Spencer) and Julia (Hara Yannas) kiss goodbye after making love in the Headlong production of 1984 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company's Lansburgh Theatre. For Julia, sex is a political act: "They want to abolish the orgasm" she says of Big Brother. Photo by Ben Gibb, Shakespeare Theatre Company.

Winston (Matthew Spencer) and Julia (Hara Yannas) kiss goodbye after making love in the Headlong production of 1984 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company's Lansburgh Theatre. For Julia, sex is a political act: "They want to abolish the orgasm" she says of Big Brother. Photo by Ben Gibb, Shakespeare Theatre Company.In 1984, in which the Party is hording real chocolate and coffee and other goods while rationing poor substitutes to the people, the novel proper ends with a fatalistic view that Big Brother cannot be beaten. However, Big Brother is always, eventually, defeated through the inevitabily of the population's greed and independent thinking classhing with the government's innate greed and thought control. The novel's own appendix suggests such an eventuality, but as Icke and Macmillan point out, that does not necessarily make for a hopeful narrative—we can't be sure that in the appendix itself the cycle is continuing.

The appendix focuses on the Party's primary weapon in thought control: Newspeak and changing the historical record. Look around you; or, more precisely, listen around you, to examples of Newspeak in today's culture. To clarify, I don't mean what some people derisively call "political correctness," their derision clearly indicating a desired adherence to their own racist, ethnic, and xenophobic stereotypes. I don't condone censorship, but I also want modern societies to remember that the Nazi regime was built on its insidious use of racist language and images. My concern is less about government censorship than self-censorship: people not only don't remember—or want to remember—even what the Nazis did to certain populations, let alone what we did in our own national history. Some actively try to change the historic record. In the face of facts, they create new facts out of whole cloth that they keep repeating with the aim of establishing them as the true record—at least for their own faction. We see it in the efforts to strike the realities of slavery in America and the Holocaust in Europe from the historical record, but I have been most confounded by politicians and their followers' attempts at rewriting the record of America's birth, trying to rewrite the intents of our Founding Fathers even though the convictions of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and others literally are etched in stone here in Washington, D.C. Some school boards have gone so far as to unpeople Jefferson in their history textbooks.

What 1984 tells us is that we cannot sit in our comfortable chairs and point disdainfully at the totalitarian regimes of North Korea, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, and the Taliban without noting the kind of intensely ideological and demagogic partisan politics enwebbing us with thought-control tactics here at home in North America and Europe (and with the word demagogue I am not referring to one specific individual: a half dozen come immediately to mind in my homeland and a half dozen more in Europe). Day to day, even, the historic record is being rewritten, truth is kneaded into new forms, and individuals of dutiful national service are being unpeopled. Scarily, much of the public is buying into it. Big Brother is something much more than government surveillance and intrusion into private lives; it is the thought police. And in Orwell's universe, the line between Big Brother and its opposition, the Brotherhood, is blurred, if it exists at all.

"How could you communicate with the future?" the Host in the play 1984 says as he ponders over Winston's diary. "Either the future would resemble the present, in which case it would not listen to him: or it would be different, and his words would be meaningless."

Or both.

Eric Minton

March 22, 2016

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances