Twelfth Night

A Dying Fall Resurrects As a Great Play

Shakespeare Theatre Company, Sidney Harman Hall, Washington, D.C.

Monday, November 20, 2017, N–22&24 (orchestra right)

Directed by Ethan McSweeny

When the plane crashes, the audience applauds—raucous, prolonged applause. Right up front I want to point out that disturbing observation of humanity's schizophrenic nature. I didn't clap, though I admit I had just witnessed as impressive a theatrical moment as I've ever seen on any stage, anywhere.

As Olivia (Hannah Yelland, left) watches in fascination, Viola (Antoinette Robinson) disguised as Cesario, says she will halloo Olivia's name to the reverberate hills in the Shakespeare Theatre Company's airport-set production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night. Photo by Scott Suchman, Shakespeare Theatre Company.

Not that this is your typical theater stage. It's an airport departure gate waiting lounge. Scenic Designer Lee Savage's authentically detailed set occupies the Shakespeare Theatre Company's (STC) Sidney Harman Hall stage plus some, as the play space has been expanded into the theater's orchestra seating, displacing patrons from the first few rows to bleachers on each side of the stage. A Christmas tree with red bowls and purple ornaments stands on a ribbon-decorated utility cart in the middle of this lobby with gift-wrapped packages surrounding the base.

The audience is still moseying into the theater when the airport's cleaning guy pushes his cart into the boarding area. It's a typical cleaning guy's cart, with trash bin, supplies, and a guitar. The name tag on the man's blue coveralls identifies him as "Feste." Passengers begin arriving: a guy with flowers in his backpack; a woman wearing a black suit and sunglasses, a black scarf covering her head; a military member in his camouflaged uniform; a young man with a guitar; a woman with a stroller and a young girl in tow; a young woman snapping photos. They all gaze at the list of flight departures on hanging video screens and then find seats. Flight attendants pass through. A guy in a Hawaiian shirt, shorts, and a straw hat strolls in. Another man with jacket flung over his shoulders barks at the skycap maneuvering a cartful of luggage. In comes a big dog crate; inside is a little dog. A guy walks in, sneaks up behind the young woman taking photos, touches her on the shoulder to make her turn the wrong way, and, when she sees who it is, they hug. They then get another man—who has been displaying a jittery fascination with the woman in black—to take their picture.

Feste pulls the Christmas tree to the back corner. A boarding queue is set up and preboarding announcements crackle over the loudspeaker: no photography, silence cell phones, and "thank you for choosing Shakespeare." Boarding by zones begins. Meanwhile, Feste with guitar begins singing, and as he moves to the balcony, the boarding lounge empties and in seamless succession the seats are rearranged as airliner seating filled with passengers. The plane starts pitching with rough turbulence and seems to go into a dive as Feste nearly screams his song's final line. Then chaos: the passengers scatter, upending all the seats, and luggage falls from the ceiling and hits the stage with a sickening thud. Then, raucous applause.

And then: "What country, friends, is this?" Viola (Antoinette Robinson) lying amid the scattered luggage speaks as she looks up and around. She is in Illyria, and we are into William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, or What You Will. I normally don't give the secondary title when I review productions of this play, but what you will, and what we will, is an important thematic subtext to this particular staging ingeniously helmed by Ethan McSweeny in which the doomed flight framework is integral. Yet, even with some odd character transfers and scene rearrangements (like starting with Viola landing shipwrecked—er, planewrecked—in Illyria, then doing scene three introducing us to Sir Toby Belch and company at Olivia's house before circling back to scene one with Orsino's famous opening line, "If music be the food of love, play on"), this is Shakespeare's play in tone and, most importantly, in humor. An audience cheering a plane wreck is no more schizophrenic than laughing at the circumstances Shakespeare created for his characters in this his most sublime of comedies.

Using death as a framework for Twelfth Night and Illyria as Viola's state of mind has been done before—nearby and not long ago, in fact. McSweeny's staging resembles that of Taffety Punk's 2013 production of Twelfth Night, or WHAT YOU WILL (the subtitle outsizing the main title in playbills) a couple dozen blocks from Sidney Harman Hall. Both productions open with happy passengers in transit before dramatic presentations of the wreck (ship in Taffety Punk, plane here) that concludes with Viola's first line asking where she is. Both return to the scene of the catastrophe at play's end. More notably, both also use Feste as an omnipresent character with spiritual qualities, speaking the lines of the sea captain in Viola's first scene, telling her "This is Illyria, lady," describing her brother Sebastian's possible survival, and explaining the landscape on which she has landed. In Taffety Punk's production, the character was rechristened in the cast list as "Death, as Feste," while here Feste (Heath Saunders) remains the cleaning guy in the airport lounge—he doesn't board the plane. Taffety Punk set the play under water, as if Viola had either drowned or is drowning as she lives through her adventures in Illyria. STC puts all the action in the boarding lounge. Sir Toby Belch (Andrew Weems), wearing robe and shorts, gets his liquor from the flight attendant's refreshment cart; the luggage strewn about the stage serves as props; and the Christmas tree becomes the box tree in the Malvolio letter scene.

Even if McSweeny borrowed his ideas from Taffety Punk's production (but, really, there are few new ideas in staging Shakespeare, just different executions), he scores his own points by successfully translating it into the anachronistic setting of airline travel. His intent is both thematic to the play and purposeful to the D.C. audience's experience with airports, one of which is less than five miles from this theater. "When Shakespeare set this play in Illyria, he was going to the farthest-out place he could think of," McSweeny writes in his program notes. "If Illyria is where we would ultimately be going, we had to start somewhere else, somewhere more grounded in reality, a world more like the one we're living in." He not only seized on Sidney Harman Hall's hitherto underutilized potential for a variety of stage configurations but on the building's glass-fronted architecture. To McSweeny, "Sidney Harman Hall and its public spaces are reminiscent of the international departure lounge at an airport. It is an appropriate metaphor really—the theater as a point of departure."

The airport setting also gives this Twelfth Night a keen psychological quality. Audiences settling into their seats can watch the activity in the boarding lounge and try to identify the play's characters (from my descriptions above, you might identify some). We do something similar in real airport boarding lounges, eyeing the characters around us, making conclusions about their life stories and what they might portend for our upcoming flight: Will they be sitting behind me prattling? Is he going to crash Zone One boarding? Is she going to hog the bin space with those two oversized bags plus her briefcase?

McSweeny's product has another important resemblance to the Taffety Punk production of four years ago: the quality of the performances and the pleasure of the overall experience. Despite what seems to be Viola's death at the outset, McSweeny keeps the comedy front and center, and he's gathered a talented corps of actors to carry it off. Twelfth Night is an ensemble play with so many richly comic roles that any one of eight characters could be considered the show's star, resulting in reviews that read like a grocery list of the corps' ingredients. I'll highlight a couple of stand-out characterizations, starting with Jim Lichtscheidl as Sir Andrew Aguecheek. He first appears as a tennis-playing hippy with a Bjorn Borg headband and too-tight shorts. In his first scene with Toby, Lichtscheidl turns his racket into an air guitar (accompanied by a real guitarist up in the side balcony) as he brags about his abilities dancing the galliard and cutting a caper. Aguecheek later appears in polo gear, then with golf clubs (using tiger club covers), and, when he's preparing to duel with the supposed Cesario (Viola in disguise), wearing rose-embroidered formal fencing gear. Lichtscheidl's Aguecheek fully personifies the lines Shakespeare wrote for him. Before the duel—which the now-frightened Aguecheek is deathly afraid of fighting thanks to Toby's machinations—Toby tells him to "stand here, make a good show on't," so Lichtscheidl does a little soft-shoe dance that even Toby finds incredulous.

The production is replete with such moments, some textually inspired. Toby's "four elements" becomes a line of cocaine. When Olivia (Hannah Yelland) sends Malvolio after Cesario with the ring she claims the boy gave her, Yelland has trouble pulling the ring off her finger, signaling her impetuosity in the moment. Some such golden moments, on the other hand, are products of the production's imagination. In the gulling scene, Malvolio (Derek Smith) never spots the letter placed before him, so the conspirators, hiding behind the Christmas tree, thrust it through the boughs at his eye level. Malvolio looks in the direction of the letter with a puzzled expression, then steps forward and adjusts the bow next to the paper before continuing on with his prattling daydream. The conspirators finally use Aguecheek's polo club to drop the letter on Malvolio's head.

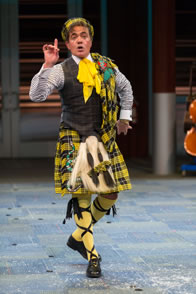

Smith gives an acute reading of Malvolio, arrogant (even toward Olivia—he can't help himself) and full of self-love. Nevertheless, his great pride comes from his sense of duty and place in the household, a place, which includes the complete confidence of Olivia—that, for this Malvolio, is a degree to love. Normally stiffly dressed in a checked three-piece suit (even when roused at night), Smith's Malvolio defies anachronism when he falls for the prank in the letter by proudly wearing a yellow-and-black plaid kilt, his yellow stockings cross-gartered (Costume Designer Jennifer Moeller deserves star billing for her work across the cast). Malvolio's cell, by the way, is that dog crate we saw in the preshow, covered by a tarp to create his darkness.

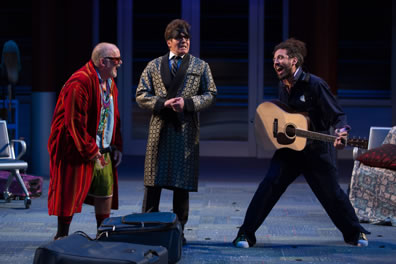

Above, Sir Toby Belch (Andrew Weems, left) and Feste (Heath Saunders, right) sing annoyingly to Malvolio (Derek Smith), whom they've roused in the middle of the night with their revelries in the Shakespeare Theatre Company's production of William Shaksepeare's Twelfth Night. Left, the duped Malvolio appears to Olivia in yellow stockings, cross-gartered. Photos by Scott Suchman, Shakespeare Theatre Company.

Despite being an ensemble piece, Twelfth Night is clearly Viola's play; all plot strands twine through her or her twin brother Sebastian (Paul Deo Jr. in a confidently commanding performance) mistaken for her. Robinson gives Viola hip suaveness in her disguise as Cesario, dressed in a green suit with orange, ladybug-decorated tie. It's a bravado that masks not only her real identity as a young woman but her emotional yearnings for Duke Orsino. Bhavesh Patel plays a manic duke, too often seeming on the verge of erupting into violence. Yet, wearing a marbled suit with his like-dressed attendants zooming around on scooters, Patel's Orsino does emote an exotic aesthete in his speech and bearing. His keenest moment comes when Viola talks about a sister. "And what's her history?" Orsino asks. Patel charges the line with rapt intrigue that there could be a female version of Cesario, turning a simple piece of text into a key indication of his attraction to the disguised Viola.

The performance that emerges as this Twelfth Night's star role is Saunders as Feste. He gives a cynically droll delivery of Feste's quibbles and puns, especially in his word games with Cesario, but he adopts a tone of other-world indifference when he takes over the lines of characters dropped from the play, such as the seaman in Viola's first scene and Valentine in Orsino's court. He takes on the role of the priest who marries Olivia and Sebastian, (whom Olivia believes to be Cesario), the ceremony taking place on stage with Saunders employing flight attendant safety message gesturing. This blurring of characters has a comic payoff, first when, right after this scene, Feste regards with great puzzlement Viola/Cesario as he encounters her attending the duke. Then, standing at the back of the stage when Olivia calls for the priest, Saunders gets a laugh with his realization that he must somehow make a quick change right in front of us. However, where Saunders soars most is with his musical skills. The production's unarguable highlight is Saunders' Feste singing "Come Away Death," accompanying himself on cello and joined in duet by Music Director Matthew Deitchman, playing Curio, on guitar and high harmonies. The two turn the song into an acoustic power ballad, so moving it earns its own prolonged, raucous applause, restoring my faith in humanity.

The production falls into one unfortunate trap with McSweeny's decision to give Maria (Emily Townley) a daughter and assign that young girl the role of Fabian. She takes part in the gulling scene, which is problematic enough; but when Malvolio, studying the handwriting, determines it to be Olivia's through "her very C's, her U's, and her T's, and thus makes she her great P's." When this crude joke passes through the young girl Fabian, the audience's silent reaction is deafening. Several of Fabian's passages are given to other characters, though she is allowed to read Malvolio's letter in the final scene, needing some help with some of the phrases from Feste.

One trap McSweeny brilliantly avoids is the ghost of clunky Sidney Harman Hall productions past as he turns the theater into what I never thought it could be, a great play space. The secret is not just the set but also making sure actors understand how to play to all angles, even in corner alcoves; even characters waiting in the wings inspire chuckles with their antics (past STC shallow-thrust productions I've attended here have ignored the patrons on the sides of the stage). Poignantly, upon learning how he has been "notoriously abused," Malvolio exits the final scene through the auditorium: He is in the the middle of the audience when he turns to shout, "I'll be revenged on the whole pack of you."

As Feste leads the ensemble into singing the closing number, "For the rain it raineth every day," the cast moves to the balcony, leaving Viola alone on the stage. Snow starts to fall. Viola lies down, as first we saw her after all that luggage dropped from the heavens, and it's the image we are left with as Feste and company sing the song's last stanza:

A great while ago the world begun,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain

But that's all one, our play is done,

And we'll strive to please you every day.

You might think she has been dead all the while. However, listening to the song here—which so many critics see as a dark denouement—I hear a celebration of life. And the feeling we are left with as the lights fade is that it has been a life well spent.

Raucous, prolonged applause.

Eric Minton

December 5, 2017

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances