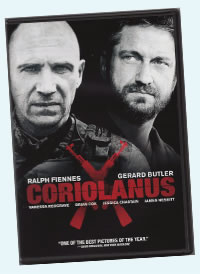

Coriolanus

Fiennes Finds the Present

In Shakespeare's Ancient Roman Tragedy

Weinstein Company, Hermetof Pictures, Magna Films, Icon Entertainment International (2011)

Directed by Ralph Feinnes. with Fiennes, Gerard Butler, Vanessa Redgrave, Jessica Chastain, Brian Cox, Paul Jesson, James Nesbitt.

Video images of protestors demanding more economic equilibrium, of rioters angry at austerity measures, of armed warfare with soldiers fighting in the streets contending with snipers and improvised explosive devices, of staged public debates among candidates vying for national office. This is CNN.

This is Coriolanus, too. Ralph Fiennes, a longtime Shakespearean veteran of the English stage, makes his film directorial debut and takes on the title role in a modern-set Coriolanus inspired more by the storytelling techniques of cable TV news, YouTube, and CSI than theatrical traditions. As a filmmaker, Fiennes has a bit more to learn, but as a Shakespearean, he has a ton to teach. Thank goodness he chose to start with Shakespeare's most complex tragedy, whose hero's tragic flaw is that he's too heroic—that, and he's a momma's boy. What we get is not only an apt telling of Coriolanus but a five-star Shakespeare film.

Menenius (Brian Cox), Coriolanus (Ralph Fiennes), General Cominius (John Kani), and the senators head toward a meeting with the citizens in the movie Coriolanus directed by Fiennes. Though using modern dress and techniques, Fiennes stayed true to Shakespeare's text. Photo by Larry D. Horricks, The Weinstein Company.

With its modern setting and interspersing television and Internet images, Fiennes' film illustrates the universal themes Shakespeare explored in Coriolanus: the dangers of self-hero worship, the fickleness of a people, the political manipulations of messages and images, the quick-to-conflagrate nature of mobs, and the precarious tightrope nations travel between dictatorships and republics. Shakespeare set his play in the early days of the Rome Republic, which was then fending off a neighboring tribe on the Italian Peninsula, the Volsces, but he could have been writing about his own England only recently unified with Scotland. Fiennes' version shows us that similar political dramas are playing out in England today, too, as well as in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Greece, and the United States.

Notably, Fiennes filmed much of the movie in Serbia and Montenegro. A budget consideration, perhaps, but in doing so he used locales still suffering from recent tribal warfare and civil strife of the type Shakespeare portrayed between Rome and the Volsces and between Rome's patricians and its populace. When we watch the battles and riots play out on the newscasts in Coriolanus, we don't sense we're watching Shakespeare, per se; we're genuinely re-living scenes we've witnessed in the past 15 years.

Make no mistake, though, this is Shakespeare’s play. Fiennes and screenplay writer John Logan trimmed about half the text, but they made sure the verse that remained was treated with wholesome respect. In the play’s opening scene Shakespeare presents a mob being addressed by Menenius; Fiennes films this scene as a group of students meeting in secret and watching Menenius, “one that hath always loved the people,” on TV giving his address in an interview. Similarly, Shakespeare opens II.2 with two unnamed officers, “lay[ing] cushions, as it were, in the Capitol” discussing the merits of Coriolanus’ candidacy for the consulship; Fiennes puts this debate in the mouths of two pundits on a Fox News–like show. This could all come across as gimmickry except that Fiennes is a devotee of Shakespeare’s texts, so the devices and images he uses specifically serve Shakespeare’s purposes (after all, Shakespeare used two gossiping officers laying cushions merely as a device to conveniently lay out the issues concerning Coriolanus’ candidacy; Fiennes does the same thing with a contemporary device).

At the center of all this is Caius Martius, later surnamed Coriolanus for his exploits at the battle of Corioles, a man who is undoubtedly a hero to his country: we see it and we hear of it on all sides, including from both his military enemies abroad (Aufidius, the Volscen general) and his political enemies at home. Coriolanus is also undoubtedly egotistical and out of touch with his nation's working class; we hear of it even from his closest friends, and we see it. On a theater stage or in reading the play, the sway of events that end up undermining such a war hero as Coriolanus comes so quickly it can be confusing. By presenting these events as if they were newscasts, viral Internet videos, and staged televised debates, Fiennes makes sense of it all.

“So our virtues lie in th’interpretation of the time,” says Aufidius, a line that serves as this movie’s foundation. For 24-hour cable news channels, Twitter, and the Internet have condensed our concept of time in the same way Shakespeare artificially condensed timelines in his plays. In our current news time paradigm we see the fickleness of “the people” play out daily, candidates slip up and down the polls in double-digit leaps and stumbles over the course of three days, and a political outcry against the president turn into a crushing defeat for his overreaching political opponents within a week. We see powerful individuals pull media strings to manipulate images, and we see a populous reacting only to the veneer and sound bites, their thus-informed opinions easily buffeted by contrary opinions told in catchier slogans and more intense visual images. When the two tribunes, Sicinius and Brutus, tell Coriolanus the people have risen against him within hours of his earning their accolades in the marketplace, Fiennes plays Coriolanus as incredulous in asking “What makes this change?” Newt Gingrich could sympathize.

Modern setting, modern feel, but Shakespeare’s verse; there is no disconnect because of the cast Fiennes has assembled, starting with himself. You thought Voldemort was scary? When Fiennes’ General Martius steps out from behind a wall of riot police shields, strides up to the leader of the student protest and speaks his first line in the play, “What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues, that, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion, make yourselves scabs?” we, like the youth leader, both recoil in fear but brace in admiration at the general’s sheer force and presence. This moment sets a standard from which Fiennes never once falters to the end.

Volumnia (Vanessa Redgrave) kneels before Coriolanus to plead for Rome as Aufidius (Gerard Butler) watches in the background. When Volumnia gets Coriolanus to capitulate, Aufidius seizes the moment as an opportunity to bring down Coriolanus himself. Photo by Larry D. Horricks, The Weinstein Company.

His only match is his mother, Volumnia, played by Vanessa Redgrave. Dressed in her own army uniform, she indicates clearly that her son is herself reincarnated. And he believes it. In the supplication scene as Coriolanus prepares to sack Rome, having allied himself with the Volsces upon his banishment from Rome, Volumnia finally gets him to crack as she roars, “This fellow had a Volscian to his mother.” In the relationship established by Redgrave’s Volumnia with Fiennes’ Coriolanus, this line is more than a mother disowning her son; she’s stripping her son of his only remaining identity. This relationship so overshadows that of Coriolanus with his wife, Virgilia, that Shakespeare does the latter short shrift in his portrayal of her. Jessica Chastain, however, rescues Virgilia from obscurity, giving her a heroic presence as she feels more heartfelt love than duteous honor for her husband (a portrayal abetted by Fiennes providing an additional scene of intimacy between them). Chastain’s Virgilia comes to regard her mother-in-law as a greater enemy to her marriage than Aufidius and the Volsces.

Despite the superb performance of Fiennes and Redgrave, Brian Cox steals the spotlight with his performance as Menenius. In his hands is the portrayal of a politician who remains a constant ally of Coriolanus but also earns the genuine respect of the people and Coriolanus's political enemies. Whether he's addressing the mob via a TV interview, bantering with the tribunes in a bar, or whispering wisdom into Coriolanus' ear, Cox displays the deftest of touches with Shakespeare's verse while imbuing his character with genuine appeal. Paul Jesson and James Nesbitt play the tribunes as slippery, smarmy politicians, yet, as the best of politicians will do, they manage to act their public parts with perfect aplomb.

The only weak link in the cast is Gerard Butler as Aufidius. It's easy to understand why Fiennes cast an action flick idol in the role of the one warrior who can match Coriolanus in both generalship and hand-to-hand combat, but it comes at the cost of a skilled verse speaker (ironically, Butler's first acting role was in a stage production of Coriolanus, but after that he has no Shakespeare listed in his bio). Butler inconsistently applies a brogue to his lines, and we fail to discern early on the genuine respect he has for his most loathed enemy. But Butler does requite himself by movie's end when, after embracing the banished Coriolanus as an ally, he comes to see firsthand the very pride that led to Rome banishing Coriolanus in the first place. When Volumnia gets Coriolanus to capitulate, Butler's Aufidius does not play the moment so much as a betrayal than as an opportunity he'd been looking for to bring down Coriolanus himself; he may not earn the spoils of sacking Rome, but he'll regain the regard he once held unshared among the Volscians.

Power, en total or in niches, is the sole aim of most of the players in Coriolanus. Menenius, alone, seems to put service before self, and to highlight this, Fiennes makes a questionable departure from the text by having him commit suicide upon his failure to sway Coriolanus in his assault on Rome. In Shakespeare's version, Menenius welcomes home the women after their triumph over Coriolanus, but Fiennes chose to glance past this ironic turn in the story—the woman who created Coriolanus contributes most to his destruction—and focus wholly on the tragedy of the hero. His Coriolanus exists in a philosophical realm where service and self are one and the same; there is no one before the other. He may claim that duty to Rome is his motive and he may believe that claim himself, but his singular self-view of service for one's own glory, drilled into him by his mother, ends up disregarding any other viewpoint or way of life. This drives him to his triumphs, it has him driven out of Rome, and it drives him to his destruction in the end.

The last image Fiennes gives us in his Coriolanus is the hero’s body being thrown into a truck bed. This image draws more from another Shakespeare play than this one: “There’s honor for you,” Falstaff says over the dead Sir Walter Blunt in Henry IV, Part 1. Caius Martius Coriolanus served Rome for his own lasting glory; he ended up just another political outcast and war fatality. His time passed. Quickly.

Eric Minton

February 24, 2012

Now on DVD

Now on DVD

The DVD of Ralph Fiennes' Coriolanus comes with only two extras, a short making-of documentary and a commentary track by Fiennes. Depending on what you look for in these commentary tracks, this one may or may not be accurately called an extra.

Fiennes, ever humble, comes across as a professor lecturing on his interpretation of the play and how his interpretation manifests in the film. Consider him a suitable expert, and as Shakespearean study the commentary track is a worthy classroom aide. But he offers scant insight into the actual filming and only one production anecdote—so don’t look for any good filmmaking gems or gossip here.

And what he offers about filming in his Balkan locations leaves you wanting so much more: tidbits like his using the Serbian Army’s anti-terrorism unit to play both the riot police and Roman army, or how his filmed version of the capitol steps riot using just a handful of extras was juxtaposed with archival newscast footage of a full-scale anti-Milosovic riot on those very same steps. His most revealing insight, especially for a man with an exalted Shakespearean acting career and experience playing Coriolanus on stage, is his assessment of the performances of Vanessa Redgrave and Brian Cox. Their verse-speaking skills inspired everybody on the set, Fiennes says, himself included.

Certainly, Fiennes’ interpretation of the character and play contribute to a fuller understanding and appreciation of Coriolanus. Still, rather than constant adulation and frequent re-reciting of lines spoken in the movie, he could have used that time for some “how we did this” and “how we played that” commentary, providing us a fuller understanding and appreciation of HIS Coriolanus.

This is quibbling, though. The real reason to get this DVD is to have this outstanding film in your Shakespeare library. Watching it here for the first time since I saw it in a cinema six months ago when I gave it five stars, I admire it even more now. I was perhaps unfair to Fiennes the director in my initial review, for this is an A+ Shakespearean film, and his touch along with his interpretation and his performance make it so.

Eric Minton

June 27, 2012

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom