The Gospel at Colonus

A Sermon from the Book of Oedipus

By Sophocles, Adaptation and Lyrics Lee Breuer, Music and Lyrics Bob Telson

WSC Avant Bard, Gunston Arts Center Theatre Two, Arlington, Virginia

Thursday, March 8, 2018, second row, center of middle section of theater-in-the-round

Directed and choreographed by Sandra L. Holloway, original direction by Jennifer L. Nelson

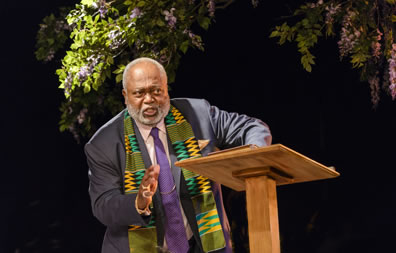

Singer Oedipus (Kenton Rogers) seeks his way toward death in WSC Avant Bard's production of The Gospel at Colonus. Below, Preacher Oedipus (William T. Newman Jr.) preaches from "The Book of Oedipus," and the cast along with the Women's Ecuminical Choir sing the finale. Photos by DJ Corey Photography, WSC Avant Bard.

Praise the Lord and Greek theater! Praise WSC Avant Bard, not only for bringing The Gospel at Colonus to the stage in the D.C. region, but for reviving it a year later, too, giving me a chance to take in this theatrically spiritual experience.

I was introduced to this—well, what do we call it? play, musical, Pentecostal service?—in a Masters of Humanities class in the mid-1990s when the professor showed us a telecast of it. To this day I don't know why he shared The Gospel at Colonus with us. I mean, yeah, it's about Oedipus and society and human nature grappling with greed, empathy, desperation, devastation, triumph, those pesky fates and, ultimately, redemption. But I believe the professor simply wanted to share The Gospel at Colonus with us. Amen to that. For I was moved by it and became an instant fan of the Five Blind Boys of Alabama featured in it.

When WSC Avant Bard mounted its intimate production last year, I wanted to see it but couldn't fit it into my schedule, even though its run was extended. So popular and acclaimed was the show, the company revived it for this season. Second chances are rare gifts indeed, so this time, though my schedule is even more crowded this year, I simply bullied it onto my calendar. Amen to that.

Lee Breuer (book and lyrics) and Bob Telson (music and lyrics) first adapted Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus into a Pentacostal church service format for the Brooklyn Academy of Music's (BAM) Next Wave Festival in 1983. A visiting preacher sermonizes from "The Book of Oedipus" while other church officials assume the tragedy's roles: Singer Oedipus, Evangelist Antigone, Pastor Theseus, Singer Ismene, Deacon Creon, and Testifier Polyneices, plus, of course, a gospel choir. Morgan Freeman, by the way, originated the role of Preacher Oedipus, and the initial production made it to Broadway in 1988.

This is no acid trip. Scholars have long noted the musicality (let alone the spirituality) in Greek tragedy. A group of Florentine scholars in 1597, riding the Renaissance wave of rediscovering Greek and Roman classicism, sought to revive Greek theater on their thesis that the Chorus, if not all of the parts, were sung: They ended up inventing a new art form, opera. Oedipus at Colonus probably could translate into jazz, rock, and hip-hop, too; turn it over to Timberlake and Timbaland and see what they come up with. But Gospel music and, more than that, the Pentecostal format is what moves you, whether the preaching comes from the Bible or from "The Book of Oedipus." "I know it was hard, my children, and yet one word frees us of all the weight and pain of life. That word is love." Preach, Preacher Oedipus!

WSC Avant Bard, as the name and its slogan, "Theater on the edge," indicate, strives to present "the best of world drama in productions that challenge audiences to see the plays' meaning and relevance in a new light," as the company's Artistic and Executive Director W. Thompson Prewitt writes in his program notes. Though 27 years on, WSC Avant Bard still has the air of a fledgling theater company, with eager, daring, youngish theater artists doing edgy productions in small studio spaces. Avant Bard's Shakespeare productions certainly challenge our familiarity with the plays, if not always satisfyingly so. Generally I appreciate the company's artistic verve and I certainly respect its tenacity in surviving intact some hard times that had it wandering like blind Oedipus from venue to venue around D.C. and its Northern Virginia suburbs a couple of years before finally settling in the Gunston Art Center in Arlington.

If The Gospel of Colonus is in itself a new, challenging approach to "the best of world drama," then Prewitt's don't-mess-with-it approach in bringing it to the stage was his keenest contribution. Rather than have the Avant Bard acting company have a crack at it, Prewitt turned the production over to an artistic team that would do it with authenticity, collaborating with Minister Becky Sanders and the Women's Ecumenical Choir of Alexandria, Virginia (all of whom are in the play). Prewitt enlisted Jennifer L. Nelson as director, a woman of color with more than 40 years of theatrical experience, including 11 years as the producing artistic director of the African Continuum Theatre Company. Enlisted as musical director was d'Marcus Harper-Short, who makes further contributions to the production as the on-stage piano player and taking on the role of Creon. I love his piano, but I was most taken with the effective mask of duplicity in his face as Creon makes peace overtures to Oedipus to return to Thebes (where Creon actually intends to kill him) then, when Oedipus refuses, kidnaps his daughters to leave him helpless. For the remount, Harper-Short is joined by Jabari Exum, who served as tribal dance and movement coach on the film Black Panther, on African drum.

Sandra L. Holloway, who choreographed the original production, has taken over as director of the remount, which features many of the original cast, most especially Harper-Short and William T. Newman Jr. as Preacher Oedipus. A key newcomer in addition to Exum is Kenton Rogers as Singer Oedipus, an ordained preacher and Gospel recording artist with acting credits Off-Broadway (God's Creation and Black Nativity) and across the country. Three local singer-actors are also new to the cast: Ayana Reed as Antigone, Jessa Marie Coleman as Ismene, and Gregory K. Wright as Choragos. The production has also undergone an aesthetic redesign. Tim Jones creates a set that puts the modern church amid the broken columns of a Greek temple with blooming tree branches overhead. Costume Designer Clare Parker mingles African gowns, head scarfs, and accoutrements with Sunday-best dresses, three-piece suits, and distinguished-patterned neckties.

I can't compare any of these to last year's cast, of course, but, oh my God, the music. This is soul music sung from the soul not merely vocrobatics, scaling the heights of spiritual ecstasy instead of showing off vocal gymnastics across musical scales. Rogers gives you goosebumps, Reed and Coleman make your heart beat faster, and Wright sends chills down your spine. Then there's returnee Rafealito Ross as the Balladeer, a lyric tenor whose crystalline singing brings tears to your eyes. The choir makes you nod your head, sway your shoulders, tap your feet, clap your hands, and feel the hallelujah. When Newman's Preacher Oedipus steps out from behind the podium to wrap up his sermon preaching on the significance of Oedipus's death, he channels the traditional styles of black church pastors in the sing-song lilt of his voice and the demonstrative dance moves of his upper body while his feet sometimes prance in place and stomp in spirited emphasis. In the ecumenical environment of an Air Force chapel, I grew up witnessing this kind of preaching and singing, and it was all I could do at Colonus to keep from jumping up and speaking in tongues myself—I had to remember I was in a theater.

So what makes Oedipus's story a Gospel? Just as we read in Noah and the flood, Jonah and the whale, and Jesus and his Crucifixion, we have to go to the other side of the great tragedy to seek meaning and redemption. Oedipus, solver of the Sphinx's riddle and great king of Thebes, had learned the truth of his existence: That, having been adopted as a baby, he, unknowingly, killed his father and then married his widowed mother, birthing not only their children but his siblings. His mother-wife Jocasta, "whose husband was by her husband, whose children were by her child," hung herself when she discovered this truth. Upon finding her body, Oedipus blinded himself and then, by his own previous edict directed at the then-unknown murderer of Jocasta's first husband, is exiled from Thebes, left to wander seeking a home. With this background, Preacher Oedipus, citing the "Book of Oedipus," directs us to "Exodus, where it speaks of his death in a place called Colonus, which was sacred, and his redemption there. We direct you to lines 275 through 279."

So what makes Oedipus's story a Gospel? Just as we read in Noah and the flood, Jonah and the whale, and Jesus and his Crucifixion, we have to go to the other side of the great tragedy to seek meaning and redemption. Oedipus, solver of the Sphinx's riddle and great king of Thebes, had learned the truth of his existence: That, having been adopted as a baby, he, unknowingly, killed his father and then married his widowed mother, birthing not only their children but his siblings. His mother-wife Jocasta, "whose husband was by her husband, whose children were by her child," hung herself when she discovered this truth. Upon finding her body, Oedipus blinded himself and then, by his own previous edict directed at the then-unknown murderer of Jocasta's first husband, is exiled from Thebes, left to wander seeking a home. With this background, Preacher Oedipus, citing the "Book of Oedipus," directs us to "Exodus, where it speaks of his death in a place called Colonus, which was sacred, and his redemption there. We direct you to lines 275 through 279."

No mere biblical cribbing here, as we pick up from Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus script. Oedipus, guided by his daughter/sister Antigone, endures scorn from many of the people he meets and is initially turned away at Colonus. He and Antigone are joined by his other daughter/sister, Ismene, and after their prayers and supplication, Theseus (A.J. Calbert) arrives to welcome them to Colonus. Creon shows up, and after he has kidnapped the daughters, Theseus promises to rescue them. "Like a dove, I wish the wind would lift me so I could look with the eyes of the angels for the child that I love," Singer Oedipus sings. "Lift me up, Lift me up, like a dove." Oedipus is next visited by one of his sons/brothers, Polyneices (Greg Watkins), who lost a war with his brother for the throne of Thebes vacated by Oedipus. Polyneices wants Oedipus to join with an army he's gathered to take back Thebes, but blind Oedipus sees through Polyneices' hypocrisy and turns him away. Theseus restores the daughters to Oedipus, who now is ready for his death. Where and the exact manner of his demise remain a mystery, even to Antigone and Ismene who accompany him part of the way, but initial mourning gives way to the realization that the redeemed Oedipus has everlasting peace. "Well, I'm crying hallelujah," sings the choir. "Yes, I'm crying hallelujah, I was blind, he made me see. Yes, I'm crying hallelujah, lift him up in a blaze of glory."

In her program notes, Nelson focuses on the individual at the center of the story as a hero's tale. "When adult Oedipus becomes aware of what he has done, he falls into despair, abandons his throne, puts out his own eyes, and sets out to roam blind and alone through the land, seeking the forgiveness of death," Nelson writes. "The play invites us to witness and share the king's suffering from our contemporary perspective—perhaps to find our own sense of peace." Prewitt in his program notes turns the focus around to the social perspective, applying the label of hero to the people who welcome Oedipus and comfort him. "The real test of a culture, the play suggests, lies in how it treats the weakest and most vulnerable in its midst," Prewitt writes. "As a great thinker long ago preached, "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me."

In her program notes, Nelson focuses on the individual at the center of the story as a hero's tale. "When adult Oedipus becomes aware of what he has done, he falls into despair, abandons his throne, puts out his own eyes, and sets out to roam blind and alone through the land, seeking the forgiveness of death," Nelson writes. "The play invites us to witness and share the king's suffering from our contemporary perspective—perhaps to find our own sense of peace." Prewitt in his program notes turns the focus around to the social perspective, applying the label of hero to the people who welcome Oedipus and comfort him. "The real test of a culture, the play suggests, lies in how it treats the weakest and most vulnerable in its midst," Prewitt writes. "As a great thinker long ago preached, "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me."

My hero focus turns in particular to Theseus. He welcomes the cursed Oedipus into the holy place of Colonus, he then goes to great lengths to aid Oedipus by rescuing his daughters from Creon. He does this out of good will, nothing more: after all, what can the cursed, dying Oedipus offer him? Oedipus bestows upon him a prophesy. Though it may be nothing more than his keen insight into human nature that he has gained through his own travails and travels, Theseus says of Oedipus. "I have seen you prophesy many a thing, none falsely." So Oedipus offers this vision to Theseus: "I shall disclose to you what is appointed for you and your city. A thing that age will never wear away. For every nation that lives peaceably, another will grow hard and push its arrogance, put off God, and turn to madness. Fear not. God attends to these things slowly; but he attends."

Theseus's city was Athens, the cradle of democracy, the model on which our own forefathers created the United States of America: the light on the hill, a city on a hilltop that cannot be hidden, as preached in another famous Gospel. This Gospel at Colonus, in song and spirit, preaches the blessings that come with keeping that light burning for all comers.

"Now let the weeping cease. Let no one mourn again. The love of God will bring you peace. There is no end."

Amen.

Eric Minton

March 9, 2018

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances