Henry V’s Vietnam War

A True Band of Brothers and Sisters

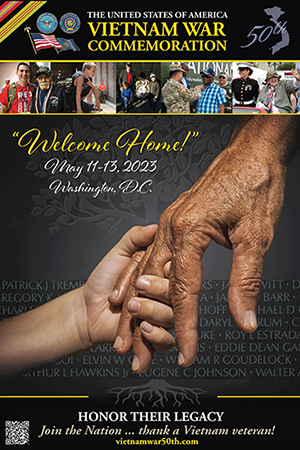

Editor’s Note: Shakespeareances.com which has been on hiatus as my wife, Sarah, slides into the last stages of Alzheimer’s, is nearing its return with a fully redsigned site. Meanwhile, for the past year, I’ve been working for the United States of America Vietnam War Commemoration in the Department of Defense, which staged “Welcome Home! A Nation Honors our Vietnam Veterans and their Families” on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., May 11-13. My job was to design, build, and manage the centerpiece of that event, Camp Legacy, featuring 98 exhibitors with historical displays, Veterans services, oral history centers, a photo gallery, a cinema (in a tent), rally points for veterans and families to gather, musical performances, and panel discussions. As the event approached, I was appointed Mayor of Camp Legacy in charge of running the operations. Throughout it all, I wondered if Shakespeare had anything to say about this gig?

Of course he did. What follows is solely my opinion and not representative of the U.S. Department of Defense or the Vietnam War Commemoration.

How do you commemorate a war as onerous as America’s involvement in Vietnam? The poorly executed strategies that led to the slaughter of more than 58,000 American men and women and the random killing of innocent Vietnamese and neutral Laotians is blood on our leaders’ hands. Yet now, the U.S. Department of Defense, as legislated by Congress in 2008, is “commemorating” the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, which officially involved the United States from November 1, 1955, to May 15, 1975. This effort is called the United States of America Vietnam War Commemoration. I currently work for the Commemoration.

How do you commemorate a war as onerous as America’s involvement in Vietnam? The poorly executed strategies that led to the slaughter of more than 58,000 American men and women and the random killing of innocent Vietnamese and neutral Laotians is blood on our leaders’ hands. Yet now, the U.S. Department of Defense, as legislated by Congress in 2008, is “commemorating” the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, which officially involved the United States from November 1, 1955, to May 15, 1975. This effort is called the United States of America Vietnam War Commemoration. I currently work for the Commemoration.

We are not commemorating the Vietnam War itself. We are commemorating the men and women—including combat forces, support units, medical and administrative personnel, air forces, riverine units, photojournalists, and chaplains—who answered the nation’s call to serve, many conscripted but choosing not to dodge. We are commemorating the families who suffered their children’s, spouse’s, sibling’s, and parent’s serving in the war, including Gold Star families whose loved ones paid “the ultimate sacrifice.” We are commemorating the 58,318 names listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (The Wall), including 1,579 still unaccounted for we cannot yet welcome home. We are commemorating the civilian communities, such as the Red Cross Donut Dollies, the USO, and the Daughters of the American Revolution who visited units in combat zones, as well as organizations, individuals, and school children who sent care packages and letters to soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and Coast Guardsmen they’d never met. We are commemorating the allies who fought alongside the United States: Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand. We are commemorating the advances in medicine and science that saved lives then and today.

Most of all, we are reckoning with an unpayable debt to the veterans and families, a long-overdue “Welcome Home! Thank you for your service.” It’s an appreciation we owe not just for their service during the Vietnam War but since. Despite the ravages of war they endured, the abuse they received upon returning home, and the government’s indifference to their ongoing pain and suffering, Vietnam veterans continued to serve the nation by serving their communities and leading the fight to make sure no veteran of any war experiences the neglect they did.

As President Barack Obama said when he established the Vietnam War Commemoration on Memorial Day 2012 in a ceremony at The Wall:

One of the most painful chapters in our history was Vietnam—most particularly, how we treated our troops who served there. You were often blamed for a war you didn’t start when you should have been commended for serving your country with valor. You were sometimes blamed for misdeeds of a few when the honorable service of the many should have been praised. You came home and sometimes were denigrated when you should have been celebrated. It was a national shame, a disgrace that should have never happened. And that's why here today we resolve that it will not happen again.

This resolve is at the heart of Camp Legacy, the centerpiece of the Commemoration’s “Welcome Home! A Nation Honors Our Vietnam Veterans and Their Families,” May 11-13 on the National Mall. Capping off the event was a multimedia concert featuring noteworthy individuals from the realms of stage and screen, sports, music, and community service.

This also is the legacy William Shakespeare wrote about some 425 years ago in Henry V.

Many people are familiar with King Henry’s “Once more unto the breach” and “band of brothers” speeches. Far fewer know his speech before the gates of Harfleur demanding the city’s surrender lest he leaves the town buried “in her ashes…enlinked to waste and desolation.” He vows to unleash his “blind and bloody” soldiers who "with foul hand defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters, your fathers taken by the silver beards, and their most reverend heads dashed to the walls, your naked infants spitted upon pikes, whiles the mad mothers with their howls confused do break the clouds.”

How much of that was part and parcel of war in Henry’s time? Or in Shakespeare’s time? How much of that was part and parcel of the Vietnam War in the time of presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon? How much is Henry’s threat given visual relevance in Nick Ut’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a shrill-shrieking daughter, then 9-year-old Kim Phuc, naked after her clothes were burned off in a napalm attack by South Vietnamese forces? How much distance separates Henry’s graphic warning to Harfleur and the experience of Mỹ Lai, whose women, children and old men were massacred by U.S. soldiers?

I grew up seeing and hearing about these images. My father was an Air Force chaplain; he didn't serve in Vietnam, but he did countless notification visits to the families of those killed or missing in action. One day he notified me of a notification he had done that day to the mother of my fourth-grade classmate. The Kent State shooting two days before my 12th birthday in 1970 is the political cornerstone of my life. I saw freedom of speech jeopardized in a nation at war with itself because of the realities of a war far away being broadcast into our living rooms with a script that made less and less sense each day.

Shakespeare delves into the juxtaposition of war’s reality and surrealness via the linked proximity of Henry V’s most famous speech and his Harfleur diatribe. Henry delivers “Once more unto the breach” (Act III, Scene 1) after the English army’s assault on Harfluer falters. Re-inspired by the king's stirring words, the English army does storm unto the breach once more. Then enters Pistol’s band of bandits notably not heading unto the breach (III.2). They serve in the war for the loot, wearing their cynicism like ribbons on their breasts. They are chased back into battle by Welsh Captain Fluellen, who is then joined by English Captain Gower, Scottish Captain Jamy, and Irish Captain MacMorris. This scene of the four captains is intended as ethnic-diversity-derived comic relief, but it has relevance to Vietnam in their arguement about how Henry is executing the war. Fluellen insists on keeping to the “disciplines of war,” meaning formal means of combat. McMorris complains that the king is not utilizing the weapons and strategies available to him. These scenes offer contending images of blind patriotism versus skeptical realism and of unrelenting enthusiasm versus exasperated exhaustion. Then comes this sequence's theatrical exclamation point, Henry’s threat of war crimes against Harfleur leading off III.3.

Let’s turn to Henry’s climactic “band of brothers” speech. Its purpose is to rally his generals on the morning of the historic battle of Agincourt. Their army, “with sickness much enfeebled” and “numbers lessened,” is facing a better-armored, well rested, and supposedly more-mobile French force. Henry looks beyond this battle about to be fought on Crispin's Day.

He that outlives this day and comes safe home

Will stand a-tiptoe when this day is named

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall see this day and live old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbors

And say, “Tomorrow is Saint Crispian.”

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words,

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remembered.

This story shall the good man teach his son,

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered,

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

Except for those last four words, this speech rings hollow for most Vietnam veterans. For decades, nobody feasted them. So antagonistic was public attitude toward them that they hid their wounds. For that matter, their most serious wounds—traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder—could not be revealed by rolling up their sleeves. Veterans wanted nothing to do with the familiar names of the war: Lyndon the President, McNamara the Secretary, generals Westmoreland and Abrams.

Rather, veterans' opinion of Kings Lyndon and Richard are reflected in William, a soldier that the incognito King Henry meets the night before his “band of brothers” pep talk. “If the cause be not good,” Williams says, “the King himself hath a heavy reckoning to make when all those legs and arms and heads chopped off in a battle shall join together at the latter day and cry all, ‘We died at such a place,’ some swearing, some crying for a surgeon, some upon their wives left poor behind them, some upon the debts they owe, some upon their children rawly left.” Henry spins a legal counterargument that the King is not responsible for the souls lost in battle for a just cause, skipping over Williams's primary point: if the cause be not good. Henry afterward, however, meditates on Williams’s point, reckoning with doubts about his moral authority, given that he’s wearing the crown his father usurped before killing Richard II (three Shakespeare plays before this one).

Above, members of the North Carolina Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association pose in front of one of their four Vietnam War vintage helicopters at Camp Legacy on the National Mall during the Vietnam War Commemoration's "Welcome Home! A Nation Honors Our Vietnam Veterans and Their Families" (photo courtesy of the Vietnam War Commemoration). Below, veterans of the Red Cross Supplemental Recreation Activities Overseas program, popularly known as Donut Dollies, join umpires and coaches at home plate during "Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans" ceremonies at Nationals Park before a game between the Washington Nationals and New York Mets (photo courtesy of the Washington Nationals).

Above, members of the North Carolina Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association pose in front of one of their four Vietnam War vintage helicopters at Camp Legacy on the National Mall during the Vietnam War Commemoration's "Welcome Home! A Nation Honors Our Vietnam Veterans and Their Families" (photo courtesy of the Vietnam War Commemoration). Below, veterans of the Red Cross Supplemental Recreation Activities Overseas program, popularly known as Donut Dollies, join umpires and coaches at home plate during "Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans" ceremonies at Nationals Park before a game between the Washington Nationals and New York Mets (photo courtesy of the Washington Nationals).

In this “A little touch of Harry in the night” scene, Shakespeare subverts his heroic portrayal of Henry by revealing the King’s own sense of shame. Such shame pervades the legacy of the Vietnam War. Not just the “national shame,” as Obama called it, but the sense of shame I’ve heard expressed among Vietnam veterans who for many years chose to stay silent about their service, tamping down their own experiences and the betrayal they felt at the hands of their government. Even my father, who never saw combat, emerged from the war with moral wounds. Notably, Henry doesn’t address the army before Agincourt, as many productions portray: the “band of brothers” are his noblemen generals—a band of literal brothers and cousins. Henry’s take on the upcoming battle’s glory foretells centuries of nationalistic spin on war’s truth.

Nevertheless, Vietnam veterans did become a true band of brothers and sisters, but not with any urging from the princes of government. The veterans forged that band on their own, through their efforts to build the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial and through their protests and political action against a government that largely ignored their psychological and medical needs. In their activism, Vietnam veterans learned that the only respect and understanding they could count on was among themselves.

And, as it turned out, from the generations that followed them. While so much of the nation swept the Vietnam War and the nation’s mistreatment of those who served in that war under the rug of time, succeeding servicemembers did not forget. “We follow in your footsteps. We serve on your shoulders,” said the 355th Logistics Group commander to a gathering of Vietnam veterans during a 2003 dedication of a memorial at Davis Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona. That speaker, presiding over the ceremony, was Colonel Sarah J. Smith, my wife. Her words have echoed in my mind ever since, and her spirit now inspires me through many once mores into the breach of this massive national effort to formally and individually thank and honor Vietnam veterans and their families for their service and sacrifice.

Fifty years is too long to wait to give those veterans a proper welcome home; a proper “thank you for your service”; a proper acknowledgment that they chose to serve their nation; a proper respect for war’s internal injuries, from blasts to Agent Orange, that has turned their service in Vietnam into a lifetime struggle; a proper appreciation for what their families went through and continue to endure. Better late than never? Not necessarily. When servicemembers returned home from the Gulf War in 1991 and this century’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Vietnam veterans greeted them at the airports, train stations, bus stations, and military bases. Vietnam veterans not only have been living up to their oath that service to the nation would never again go unappreciated as theirs had been, they don't wait even 50 hours to do so.

All of the many Vietnam veterans I’ve met in the past year have told me that, yes, 50 years is too long of a wait. Nevertheless, they appreciate our efforts, and I heard countless “thank yous” throughout those three days on The Mall as our nation finally gave them their own Crispin’s Day.

Eric Minton

May 27, 2023

Comment: e-mail [email protected]

Start a discussion in the Bardroom